LOOKING FOR AGUA IN ALL THE WRONG PLACES

Into the Altiplano (Chile/Argentina/Bolivia)

Story by Jon Bowermaster | Photographs by Pete McBride

With a team of five others – from Chile, New Zealand, the U.K. and the States – for two months we will follow a rough, 2,400 mile circuit of our own making, by foot, sea kayak and 4×4. We will often pull the sea kayaks behind us, like dogs in the harness, which may seem Quixotic here in the driest place on earth, even foolhardy.

But this is much more than just a quest for paddle-able lakes (which we will find). The motivation is to not only to seek out water – big salt lakes, high Andean rivers and streams, man-made reservoirs — but explore just how man has managed to survive here for 10,000-plus years.

The sea used to be here. Everywhere. And there are abundant signs. While our days are dusty and cold – mostly above 14,000 feet – and visited by strong winds that cease for only a few hours early each morning, they are linked by the long history of water in the Altiplano. The dry salt beds and lakes we traverse were, 2 million years before, covered by the ocean. Over tens of thousands of years as the high, long ridges of the Andes rose up, volcanically, the ocean was pushed aside, westward, its deep valleys filling with ash, lava, rock. But as recently as 12,000 years ago sizable lakes covered these Andean plains. What remains — thick salt beds, marine coral and fossils of sea life mixed in with the desert sand — are only the most visible evidence.

CHILE

T

wenty-five foot waves crash against La Portada, the 250-foot limestone arch in the Pacific Ocean, set off the Chilean coastal city of Antofagasta. With each crash, a flock of seabirds rises off the tall, whitewashed cliffs that line the nearby shore.

La Portade is probably Chile’s best-known singular piece of geography. For us, bobbing around in kayaks in rough seas under a grey sky, it represents the gateway to the Altiplano. Beyond the cliffs rise sandy hills straight up into the desert. It makes sense for us to start our search at sea level – six weeks from now we hope to be standing atop a 20,000 foot volcano – and a few days kayaking on the rough seas is a perfect, adventurous beginning.

We base on Isla St. Maria, just a mile offshore, and paddle up and down the coast. One morning we round a corner of a distant island and paddle into the middle of what in most places would be a protected marine sanctuary. Hundreds of seals, sea lions, pelicans, otters, turtles and thousands of seabirds greet us. Alex Nicks, whitewater champ and filmmaker, is almost landed on 500-pound male seal as we snake through the rock outcroppings. We hang out for several hours before making camp on the calm side of the island. The only people we see during our days on the Pacific are marisco fishermen living year-round in the small seaside town of Caleta Constitucion. They surface like hippos in the midst of offshore lagoons, wearing thick wetsuits, armed with long barbed-forks and trailing plastic pails filled with sea urchins and oysters.

Kayaks loaded onto a precarious rack atop a borrowed pickup truck, we head into the high plains from the coast, up the straight-line, two-lane asphalt that cuts across the desert. Now off the ocean, are eyes are tuned for evidence of water. The most obvious is the pipeline running through the desert, paralleling the road, buried beneath a hump of sand, re-emerging like a big, scarred-metal snake. Carrying water from high in the Andes to the mines and cities, literally emptying the scarce water sources up high, changing forever the population of the high desert. The bigger the cities grow, the thirstier the mines become, the fewer small oases towns – which have existed for centuries – survive.

We pull off in a roadside cemetery, known locally simply as “the British cemetery.” It is vast and filled with wooden crosses whitened by the heat of the desert sun. Flower wreaths of metal decorate a few of the graves; a couple of the above-ground caskets have been pried open, exposing rotted pants legs and shoes. It is the last resting place of hundreds of workers of an English-owned saltpeter mine that, in the early 1900s, lost many of its Peruvian, Bolivian, Chilean and even a few English workers thanks to disease, overwork, . . . and — surprise, surprise — lack of water.

The turn of the century was a difficult time economically in all of Latin America. People were desperate for jobs, even if it meant relocating to this inhospitable hell. Payment was usually in company scrip and the only way out for many was death.

As we poke around the cemetery I scan the horizon. Earth tones are everywhere, but mostly brown. The sky is a pale blue, thanks to already thinning altitude and dust in the air. Andean foothills appear in the far distance. It is hot and dry, wilting weather. By nightfall we will have crested 11,000 feet, where it is cold, the night air frosty.

On a blazing summer morning, the desert sky a haze of dust and heat, I stand on the lip of the world’s largest manmade hole-in-the-ground. Minding my balance, I first look deep down inside, then from east to west. It is impossible to take in the crater’s enormity without twisting my neck 180 degrees, left to right. Two miles long, half-mile deep, this massive pit – the world’s biggest, most productive, most profitable copper mine — generates one-sixth of the country’s national budget. More than 600,000 tons of copper are extracted from this pit annually $25 million dollars a day, $50 billion a year.

Jose Miguel Gonzalez was born at Chuquicamata, 27 years before, in the hospital on the mine’s grounds, built by its American parent company. The hospital has just been torn down, to make room for more mine tailing, which Jose is not happy about. “While I’m happy to see the mine growing, I hate to see that history disappear.” Truth is, the entire 1,000 family town on the mine’s edge is being torn down to make room for more digging.

The mine’s name — Chuquicamata — comes from the desert Indian tribe known for the copper kitchen utensils and weapons it created from the mineral abundant just beneath the sand. Industrialized as early as 1881, it was a US company, Guggenheim Brothers, who built the modern facilities at Chuqui, beginning in 1911. On May 18, 1915, this modern retrieval formally started.

Today everything about the place is oversized. Twenty-six tiers, each 78 feet tall, corkscrew to the pit’s floor. At the bottom I can barely make out a 210-foot-tall shovel. My guide explains that in three minutes time, with just three or four moves of its powerful jaws, it can scoop up 70 tons of slag. One ton yields just 22 pounds of raw copper. Slinking from the bottom of the mine is a four-mile-long conveyor belt, carrying waste material out. A pair of drilling rigs sit on the mine’s floor, preparing for the daily blast. At one o’clock or five o’clock each afternoon, the area is rocked by the equivalent of a man-made earthquake as strategically cored dynamite blasts shake lose more earth. The place works 3 shifts, 24/7, 365 days a year.

A dirt road spirals up around the edge of the pit. At one point I count three dozen giant dump trucks on the road, heading up out of the hole or down into it. The American-made Caterpillar trucks are as big as small apartment buildings and cost $1.4 million apiece. The newer ones can carry 440 tons and burn 140 to 150 liters of diesel per hour. The road beneath them is dark from being constantly watered by tankers spraying a mist to keep the dust down and to reduce wear on the monster truck’s tires, which cost $15,000-$25,000 apiece. The tires are 10.5-feet-tall and have a life of less than eight months. The service garage for maintaining Chuqui’s fleet is two city-blocks long, big enough to hold 25 of the 160-truck fleet at one time. The biggest challenge for the crew that services the trucks is keeping the diesel motors clean, clogged as they are constantly by desert sand and dust. The truck wash runs 24/7.

In nearly 100 years the mine has corkscrewed down nearly two-thirds of a mile and they have just recently hit water. From atop we can see a small pond leeching out of the bottom. Which means they are now cutting into the side, forcing big tunnels into the sides, to dig horizontally.

Water — obviously scarce — is recycled and used nine times before eventually ending up in acidic ponds that dot the mine. Everywhere are giant, manmade pools containing the toxic runoff of the slurrying processes. Ore is “flushed” in water with chemicals and copper floats to top – or sides – this process is repeated 9 times, to purify copper. Reflecting the sky, the water appears aquamarine blue but its cleanliness is belied by the thick black sludge that rims the sides of the holding tanks. Narrow docks reach into the center of many of the pools; on one a worker wearing an orange hard-hat stands on a platform and slowly turns a heavy wheel, lowering the level of the waste water pond. I wonder how many workers they lose each year from slipping into these ponds rich with sulfuric acid? Even the deadliest of wastewater is recycled, sprayed onto the roads to keep the dust down.

How much water do they use? Santiago is home to 6 million people; the mine at Chuquicamata, says Jose, uses as much water in one day as Santiago does in two weeks.

We began our two-month long exploration of South America’s Altiplano (high plain) by kayaking off the coast of Chile, here near Iquique. The small conceit for our adventure was to explore, by kayak and foot, the driest place on earth. Why kayaks? Because this has not always been so dry, but was all once covered by sea and lake. Everywhere we went there were reminders: coral found in the high desert, lakes rimmed with salt thanks to when the sea used to reached there.

ARGENTINA

F

rederico Norte is a squarely-built man’s man (he tells us on first meeting that he never sleeps in a tent, even at 5,000 or 6,000 meters, unless it is snowing . . .), dressed in safari outfit and drives the most tricked-out truck in all of northern Argentina. From Salta, we have hooked up with him because he is alleged to know the north of his country like the proverbial back of his hand. The second thing he admits is that he has no map, nor any specific idea of how to get where we want to go – Argentina’s largest northern lake, called Vilama. “No one ever goes there, so no, I don’t know it,” he says.

After a night camped on the banks of the (gold river), we are off, up and over 15,000 feet, over a vary bad road. The rack holding our kayaks lasts about an hour on this single-track dusty road, through wide valleys, covered with paca,. “Fucking worthless rack,” comments Frederico as we rig anew.

For most of a day we parallel the Rio Rosario, and watch domestic herds of goats, sheep, even a few cattle alongside. The Altiplano is changing here (36,000 square miles in Argentina, home to just 20,000 people), away from the big volcanoes and lakes we saw in Chile, to a backdrop straight out of a John Ford western. Towering cliffs and buttes, split by a narrow, blue river. 300 miles x 120 miles, 20,000 inhabitants.

We stop at the farm of Senor Cruz, 65, and his 2 nieces, one carrying a 3-month old baby wrapped in smoky, llama wool blanket. Cruz’s family goes back several generations on this riverside land; the five adobe buildings that are his compound – including a circular brick kitchen – are surrounded by high bluffs.

All the goats, llamas even sheep and cattle we saw feeding along the river are his. A freshly-skinned llama skin drys in the dirt, its bloody edges held down by rocks. The fences that keep his sheep in are made of llama skin. The dirt yard is littered with plastic and glass bottles, bicycle parts, an odd wool cap in the dirt.

Cruz admits he is lucky when it comes to water because the river just across from his homestead provides plenty of water year-round, though he must chop through it with an axe in the frozen winter months. He’s lived here all his life, used to be a borax worker (borax mine story)? Dark skinned and handsome, their nearest neighbors are 8 kilometers away in the town of rosario. Except that the town when we see it later is abandoned.

He seems to thrive on the dry land, with ease and tells me he will never leave here, not until he dies.

The landscape becomes evermore incredible. Changing, shifting over millions of years, creating shapes and forms almost beyond description. Evidence of cracked, exposed, raw, naked earth around literally every turn. Big mountains covered in yellos. Blue, blue skies. Solitary white clouds, volcanically-heaved and wind and glacier-carved stones, like chateaus, fortresses, restlessly as we climb up and over 15,000 feet. Sauce trees – our weeping willows.

We finally find Lago Vilama, after couple days of hard, inaccurate searching. Past many abandoned mines, skirting one “forlorn” town (guidebook language) after another “forlorn” town. Stand-alone homesteads in the middle of big flat windy plains. The only thing breaking the horizon, the only thing taller than 10 feet tall, for hundreds of miles are government-provided silver stainless steel windmills and holding tanks, for sucking water from far beneath the surface, out here where there is no water near the surface. Or the metal yellow cap of a bore hole, where someone has tested, not so long ago, for underground water. There is evidence of mine prospecting everywhere, from solitary geologists in a pickup truck, to big nomads, and piles of stone, dirt, sand . . .

Much of where we go is roadless at least according to even the best maps. Solitary white clouds, growing in size throughout the p.m., set again, blue, blue pale sky. 3-D mountain ranges. Dinosaur backs. Devil’s backbone. Color, size, shape, dimension, surreal. One constant: Volcanoes, everywhere.

Camp at Vilama is our coldest, above 14,200, with a fierce wind that whips around every corner, through any crack. From camp, our highest yet, we can see the tan/white/brown tops of mountains just across the border into southern Bolivia and the low peaks that sit just inside Chile’s border/frontier The only way to cook is for all of us is to huddle in a narrow cave, burning 100 year old moss, to create a smokey warmth. We are getting hungry, tired of pasta and rice (except for vegetarian wendy) and start coming up with slogans to push us on, over the hills, towards small towns near the huemaco canyon, where we know we’ll able to find steak au poivre. “less testosterone and more meat,” another inspired by our passing through the Chilean town of Socaire, known as the corner of the wind. “If that’s true, this must be the living room of the wind,” suggests Alex.

The morning is still beautifully cold. But by 10, as we are rigging the kayaks w/pulling rods and hunching on harnesses, the sun actually warms the cracked salt and sulfur flats beneath our feet . . . when a fast-moving off road motorcycle whizzes by, coming south from Bolivia. “The new cocaine smugglers”.

Our plan – to pull along a dry lake paralleling tall cliffs, up and over a small hill and then across salt flats to the biggest lake on the tri-border – goes quickly awry when first Wendy’s turns a 360 dumping her into/onto a cactus, up and over some particularly impressive heaps of paca brava, meanwhile, my frame has collapsed beneath the boat as I struggled to pull it over an insurmountable heap of sea grass, requiring pedro’s assistance . . . all within the first 30 steps downhill.

Once back on our wheels we are down onto a dry salt/sulfur lake, pulling alongside a 200-foot tall cliff, of brown and sand and white, across terra not-so-mucky. The day warms beautifully, as we walk and talk and haul our 100-pound loads across the salt-paned flats toward the sliver/mirage of water we can see shimmering on the far distant horizon. The wind, gusting to 20 mph, is thankfully at our backs, the sun is warm and we are headed for a big lake, so all is good.

Up and over a small hillock, now carefully wending/weeding our way through the paca brava. We look out over the 9k+ lago vilama, most of it salt-encrusted, with a long strip of open water. Lucky for us, though, the wind is still strong – gusting to 20 mph – it is mostly at our backs. And the midday sun is holding above us. The pulling is not so hard, in fact since it is not so cold, it’s pleasurable to be out.

The ground changes from thick platelets of salt to pretty thick encrusted mud-and-flamingo shit. When we pull up to the open water we send Alex out for a scout. He manages to walk across the entirety barely pulling his pants legs up. A bad sign. Which means floating the boats is going to be problematic.

Pedro and Wendy pull their boats across still mounted on the portage carts. I optimistically de-mount mine. Taking my boat off its wheels. It floats, barely. But as soon as I sit in it, it scrapes flamingo-shit and I am mired. I end up pulling across the cold water, barefoot.

So much for our highest paddle to-date. That will have to wait . . . .

Our highest paddle – 15,000 feet and cold – in the Southern Andes at the tip of Bolivia.

BOLIVIA

A

n oxtail of dirt tracks spread across the empty desert leads us to Potosi in southern Bolivia by. One-lane tracks so pocked and furrowed, washed across with blowing sand, that sometime we have to get out of the Landcruiser to scout for where the road might be.

I was drawn to Potosi – once home to the world’s largest silver mine, a city that in the 1500s rivaled London for both population and prosperity, now far down on its luck – by the miner’s market that sits at the mines entrance. Mini open-air kiosks, with aged Bolivian women selling the trio of daily necessities required by every miner: Small plastic sacks of coca leaves (their equivalent of a triple espresso), petite plastic bottles of grain alcohol (offerings to the underground gods) and sticks of dynamite (the most valuable tool of all, down under.)

Just before clambering down inside the labyrinth of tunnels that would lead us 300 feet below the surface of Cerro Rico, a pair of “pyros” showed off their own dynamite tricks. One, a kid no older than 15, lights the fuse in a stick and popped it in his mouth, like a cigarette. While the slow-burning fuse burned down he passed the dynamite among a group of tourists to have their picture taken holding a lighted stick of dynamite.

Just before it blew, he ran it downhill, stuck it in the dirt. A handful of tourists attempting to photograph the explosion are nearly knocked down by the blast.

“It’s something the police try to stop” says Adelia, “but obviously not too hard.”

We follow 14-year-old Johnny through a ragged cut in the side of the mountain, supported by centuries-old beams. With many of his peers already working 9-hour days below ground as miners, Johnny insists he’s still in school. As close as he wants to get is to work as a guide.

Thirty-three co-operatives now run the mines; the last big strike was 15 years ago. Still, everyday about 3,000 miners go underground, coca in their jaws, dynamite in their hip pocket, fingers crossed. We travel 2,000 feet into the hill, 300-400 feet through series of maze-like tunnels, lined by deep, deep pits, man-dug tunnels going back over 5 centuries ago – evidence of the early vertical shafts still exist, the ones the African slaves and later native peoples were forced to climb up and down, w/40 kilo sacks of ore on their backs – an unmappable maze of tunnels and crawl spaces and branches and dead ends, highlighted by seemingly bottomless holes on left or right, which, if misstepped into, would result in forever disappearance.

We walk, crawl, bump along, stopping only to get out of the way of miners rushing past with loaded wheelbarrows loaded with rock and sludge. Nothing mechanic, especially not jackhammers, thanks to lack of one thing desperately needed here – water. They are brusk, as workers in bad conditions should be. We try to stay out of their way.

When we stop to try and talk with them, they mostly ask for tips.

We Visit Tio Rojo and Tio Blanco, at entrance and exit of this mine, San Miguel. Cement, painted red or white, wild marbles for eyes, he is a somewhat ominous-looking god. Originated by Spaniards as a way for miners to have religion underground, began as Dio not Tio, but evolved from mispronunciation over years. On Tuesdays and Fridays the miners gather in there small caverns and pay tribute to their protective Tio. Blessing him with offerings of cigarettes, coca and alcohol, they ask for prosperity, fertility, spilling alcohol on his constantly erect cement penis, big and strong to satisfy Pacha Mama.

We ask several their ages and get a few responses of “16,” though they look younger.

“The worst thing,” says Pedro, as we watch a pair of 5 year olds play house under a rusted wheelbarrow near their shack on the side of the mine, “ is that they will never play a game. Once they are old enough to push a wheelbarrow down under, they will go.”

After chasing a couple dead ends we see a shaft of vertical light. Two hours underground, stopping to pay out coca bribes along the way way. Crawling out feels good, but we emerge into fresh air filled with the sounds of yet another anthill of men bent over picks and shovels and wheelbarrows, fingers still crossed.

Nothing but white, as far as the eye can see, the entrancing hexagonal patterns of salt formed by centuries of wind and water, tie the massive, 5,000 square mile lake into one big puzzle. The Salar de Uyuni is the largest salt lake in the world – 120 miles by 40 miles. Sitting like giant teardrop in the heart of southern Bolivia.

The Salar is an important piece in our own puzzle, of putting together the story of water here in the altiplano. Two million years ago this was the bottom of the ocean. All this salt – 360 feet deep at its thickets point – is remnant of the sea’s reduction and evaporation. As recently as 12,000 years ago we would have been standing at the bottom of a 200 foot deep lake known as Tauca.

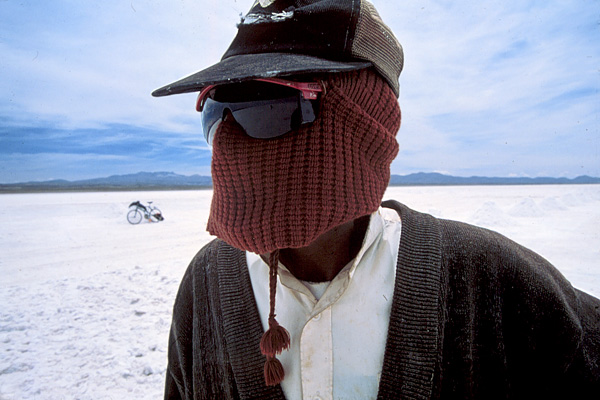

Celso Lopez Cardoso and his wife Nilda Lopez de Lopez share a bicycle, which they ride 30 minutes each way from the small town of Colchani, onto the edge of the Salar. He’s worked here since he was 8. He is 48. He lifts the piece of wool covering his face to reveal cracked/leathered skin and missing teeth. Their bike is leaning against a small pile of salt, w/lunch. We never see her face, though we hand her a pile of candies, for which she is very grateful.

Between them they will scrape 2-3 inch plots of salt, 5 meters x 5 meters, into piles about 3 feet tall. 10 a day. Initials – CL – carved into one, so that the trucks who come to pick them up know who to credit. The salar provides table salt – as well as salt for animals and even salt blocks for homebuilding – for much of Bolivia and other South American countries. They have 4 children and celso says they continue to work out here so that, hopefully, their kids won’t have to

Colchani, population 200, is a warren of adobe and salt block buildings, 1 story tall, half unfinished or crumbling. A rail line runs through town; big trucks visiting daily, carrying wood for burning/drying and delivering piles of salt and carrying away plastic bags of neatly-packaged table salt.

Town exists of 3 types of workers: those that go out onto the flats and chop or scrape the surface for salt. Truckers who drive out and fetch the salt. And “refiners,” who process, dry and bag the salt.

Constancio oversees a four-family business turning the big piles of salt into neat 1-kilo bags, headed for supermarket shelves in Sucre, LaPaz, Potosi.

The salt is moved from a big pile outside the entrance to his adobe workshop, its doorway blackened by smoke from the drying process, onto a four-foot-by-four-foot metal sheet. A fire of hot coals – fed by bundles of dry tala wood, delivered by trucks three times a week – burns beneath the metal. His grandson manning the wheelbarrow, Constancio alternates between stoking the fire and hopping onto the low-lying table and very actively moving the salt around with a flat shovel, to encourage its drying. From the drying table it sits in a pile for 24 hours and then run through a refining grinder, ready to be packaged.

Sitting beside a 10-foot tall of dried salt, a pair of adults – Felimon and Cristina – the windowless room lit only by the flame burning between them. Methodically they sweep salt into one-kilo plastic sacks, imprecisely and perfectly. With a quick flip of the wrist the bags are held to the constant flame, sealing them, and toss each into a pile that grows throughout the day. The pair will make about 4,000 bags a day. Each will earn $3-4 a day.

That night, camped on an island of tall cactus and rock in the middle of the salar we watch a sunset beyond words, the yellows and pinks and oranges reflected off the surrounding white, turning the sky deep pink and blue and purples and then the blackest black any of us have ever seen.

The refugio at the foot of Licancabur, on a hill overlooking aqua-blue Lago Verde, is a true dive. Six of us crammed into a room with three bunkbeds, the generator room on one side, a guides bunk on the other, the air thick with the smell of meat and grease, the tempest wind lifting the corrugated metal roof off its rusted nails, and slamming it back down all night long. It is so windy even the camp’s garbage dogs – especially a little poodle-like thing – are lifted off their feet as they chase scraps of cheese-stained plastic wrap across the dirt, towards the “Welcome to Bolivia” sign.

We have moved just 60 miles from Lago Colorado, yet this lake couldn’t be more different. High and cold and milky blue. From the ridge above it looks passive, calm. We paddle the first section, windless, aiming for the base of Licancabur, the nearly 20,000 foot volcano we intend to climb, if we can reach it. Which we don’t, on our first effort.

Despite that we’d been paddling nearly every day, it had been nearly 45 days since we last needed spray skirts on our boats, back when we’d kayaked around the big stone arch of La Portada on the Chilean coast at Antofagasta.

Who knew we’d need them here on what appeared at 8 a.m. on a calm, blue sky morning on Laguna Verde, 14,000 feet above sea level in southern Bolivia. Who knew that promptly at 11 a.m. every day – of course the handful of locals who lived out here in the barrenmost spot on earth, of course – that a cold wind arrived quickly and built each day until nearly hurricane proportion. We discovered this only when we were in the middle of the deceptively beautiful lake, sans skirts, with cold water blowing over our cockpits and into the boats, freezing legs, butts, hands, etc. splashing roughly and not-so-slowly filling the cockpits with freezing water.

We left the shore about 10. All was calm, and warm. Within an hour the wind was gale-force and we were digging into our cockpits and bags for hooded tops, hats and shoes.

Wind gusting between 20 and 25 mph in our faces, we are all-of-a-sudden in the most dangerous place we’ve been in six weeks. The middle of a cold water lake, far from shore, with a stiff wind blowing. One crabbed paddle, a badly-placed paddle brace, and you’re in the water. And soon suffering serious hypothermia.

For these last few days of our exploration I’d invited along Rodrigo Jordan, an old friend and one of Chile’s best-known climbers and businessman – his Outward Bound-like Vertical SA is across S. America. Though he’s been up Everest and K2, he time in a kayak is limited.

“The great thing,” I shared with him at the start of this day,” is I’m sure no one has ever kayaked here before.”

A comment he did not forget, and reminded me of when I approached him in the middle of Laguna Verde, to make sure he was alright, what with cold water pouring into his cockpit. “I can now see why no one has kayaked here before,” he shouted over the mounting wind. Nearly frostbitten when we arrived at the shore, a stiff, cold wind still blowing, all we could do was put on any piece of clothing found in our kayak and literally lie down on the ground, using the kayaks to help block the wind, to keep from freezing. Nearly hypothermic.

Forced to paddle/fight to get across its width, which was the further distance but the only way we could move, with cold water sloshing into the boats. If someone had gone over – Rodrigo? Wendy? Me? – we’d have been in serious shit. Struggling towards shore another piece of bad luck – we ran out of deep water. Two hundred yards from shore the boats are stuck in the muck, means standing out of the boats, barefoot, and pulling them to shore. When we arrive we are nearly hypothermic. The only response is to lie the boats on their side, to get out of the wind. Great. Our last lake and the first we’d been blown off.

We try again the next day, learning from our nonchalance. Hoods up, spray skirts on, from the onset. On the lake early, before what we now understood to be the inevitable wind arrived. In harness, sun-warmed and pulling the boats toward the lake, Through borax and salt and foot-deep foam whipped off the lake even the skeptical Rodrigo gets the pleasure part of what we’re doing here. Directly into the waves, splashing salt mist everywhere.

Like Colorado, I put my paddle across the coaming every once and a while, take a moment to remind myself just how beautiful this place is and what a lucky break that we are out here, on the water.

Pulling the boats, Rodrigo makes the point of how valuable a resource the altiplano could be to all 3/4 countries that share it, if they would work together to develop mineral and water resources. But the region is known for border conflicts going back centuries.

Two minutes past 2 a.m. a knock on the broken pane of glass confirms what our various alarms have already suggested. Time to get up.

We struggle, coldly, into 4 layers, stuff down jackets, harnesses, nuts and fruit, walking sticks and 4 liters of water into backpacks (plus one sizable rock, in Pedro’s pack, as exercise).

To make 5,000 foot ascent, starting at 3:30 a.m meant climbing in blackness for a couple hours. in darkness for 2 hours, Which is a good because it hides/masks steepness of the ascent. Should take 7 hours, straight up. Following in marcurio’s trudging footsteps – but we trust him since this is his 249th official climb. Coca-chewing, 57 years old, lives in small town nearby. Mismatched gloves. Mismatched poles. One a ski pole, the other a Leki – matched boots, w/holes. Green and blue one-piece suit. Nasa cap (he’d helped them lug equipment up).

The Darkness allows me to take mind off tongue chapped, climbing towards peak of Licancabur. My tongue is chapped, the inside of my mouth and nostrils badly burned, thanks to six continuous weeks hunted by fierce, non-stop Altiplano winds and sun. How bad is it? My lips are so raw that when I sleep they seal shut and pulling them apart each morning I can literally hear new skin ripping.

As first rim of light appears behind us, it silhouettes the looming peak – false peak, actually – above.

Then sunrise gives us magnificent view of laguna verde below and the sandy, mineral-stained mountains of the altiplano that surround. Gives us incredible perspective on where we have been . . . climbing is laborious but not overly difficult. M’s pace is deliberately set, and steady. He knows he’ll get us up in 7 hours, mas o menos. First half is trail through scree, the n some steep steps to get us to top of big rocks, 1000 feet above false peak. Looking out over all that we’ve seen, Pete and I “Like no place on earth.” From there, he says, it’s just another 20 minutes or so of very steep up.

A barren cactus post marks the top, which we reach in 7 hours, 7 minutes, from 14,600 to 19,600. We stand on the pebbled peak. Stone walls built by Incans as wind protection. Square Incan sacrificial hut sites nearby. 200 feet below surface, in volcanos pit, is an unfrozen lake, clean and blue and cold. Ripples of ice frozen into the rock surface, mar one side of the center. Walking out along the lips of the crater, towards the west, we can see all of our route in Chile – miniques, miscanti, lascar and more – and into San Pedro.

The great thing about our struggle to the top of Licancabur – at 19,652 the peak that has dominated our exploration and the tri-country Altiplano – was that from its flat, pebbly top, marked by the ruins of an Incan sacrificial hut, we could look out over the intersection of Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, much of the route we’d followed the past 6 weeks and nearly to the very coast where we’d begun.

At trips’ end, from atop Volcan Licancabur reached after a steep, seven-hour climb, we looked out over the sand-and-pastel-colored mountains that march for several thousand miles up the western coast of South America. We could see mineral-colored lakes in three countries we’d paddled on, as well as the tips of lakes we did not reach, as well as trickles of rivers we had only crossed. The view was stunning and left us with a lasting impression — even in the world’s driest spot, if you look hard and long enough, you can always find more than a drop of the world’s most precious resource, even in the driest place on earth.

– CREDITS –

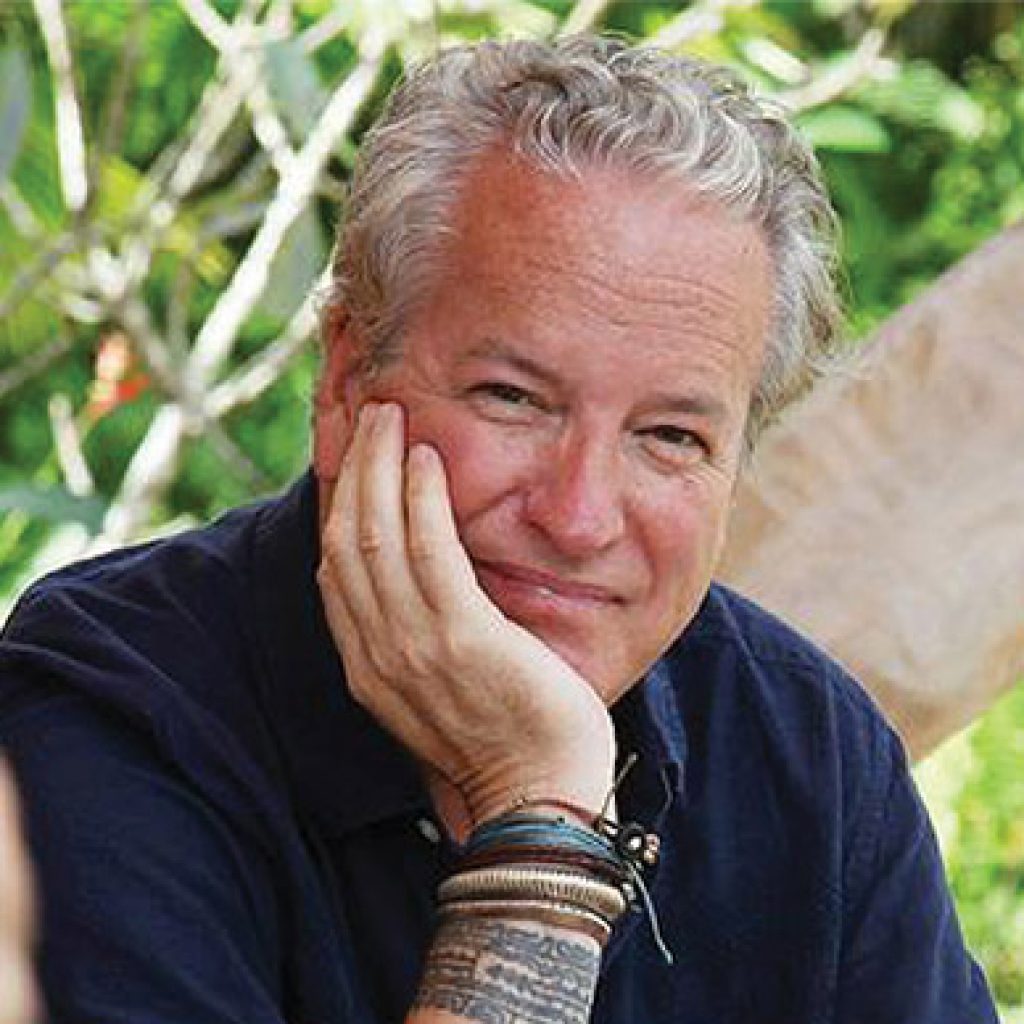

JON BOWERMASTER

Writer, filmmaker and adventurer, Jon is a six-time grantee of the National Geographic Expeditions Council. One of the Society’s ‘Ocean Heroes,’ his first assignment for National Geographic Magazine was documenting a 3,741 mile crossing of Antarctica by dogsled. Jon has written a dozen books and produced/directed more than fifteen documentary films.

PETE MCBRIDE

Colorado-based PETE MCBRIDE accompanied me on five of the eight Oceans 8 Expeditions, though our first assignment together for National Geographic Traveler was set in Cuba. In recent years Pete has continued to photograph for National Geographic and many others and has become a true hero of the Grand Canyon, having rowed it and hiked it. Check out his films, stories and images at www.petemcbride.com

ALEX NICKS

UK-born videographer ALEX NICKS is one of the world’s great expeditionary whitewater kayakers, so getting him to travel with us in our, heavy, slow-moving sea kayaks took some convincing. He filmed four of our eight expeditions; check him out here, running the Zambezi: http://vimeo.com/47919375

WENDY MADWICK

New Zealand-native WENDY MADGWICK is an ardent kayaker and physical therapist based in Chicago.

RODRIGO JORDAN

Rodrigo is one of Chile’s best known entrepreneurs and adventurers, having led two trips to the top of Mt. Everest, started a successful training company (Vertical) and a Santiago, Chile-based college focused on the outdoors and environment.