BIRTHPLACE OF THE WINDS

ALASKA: ALEUTIAN ISLANDS

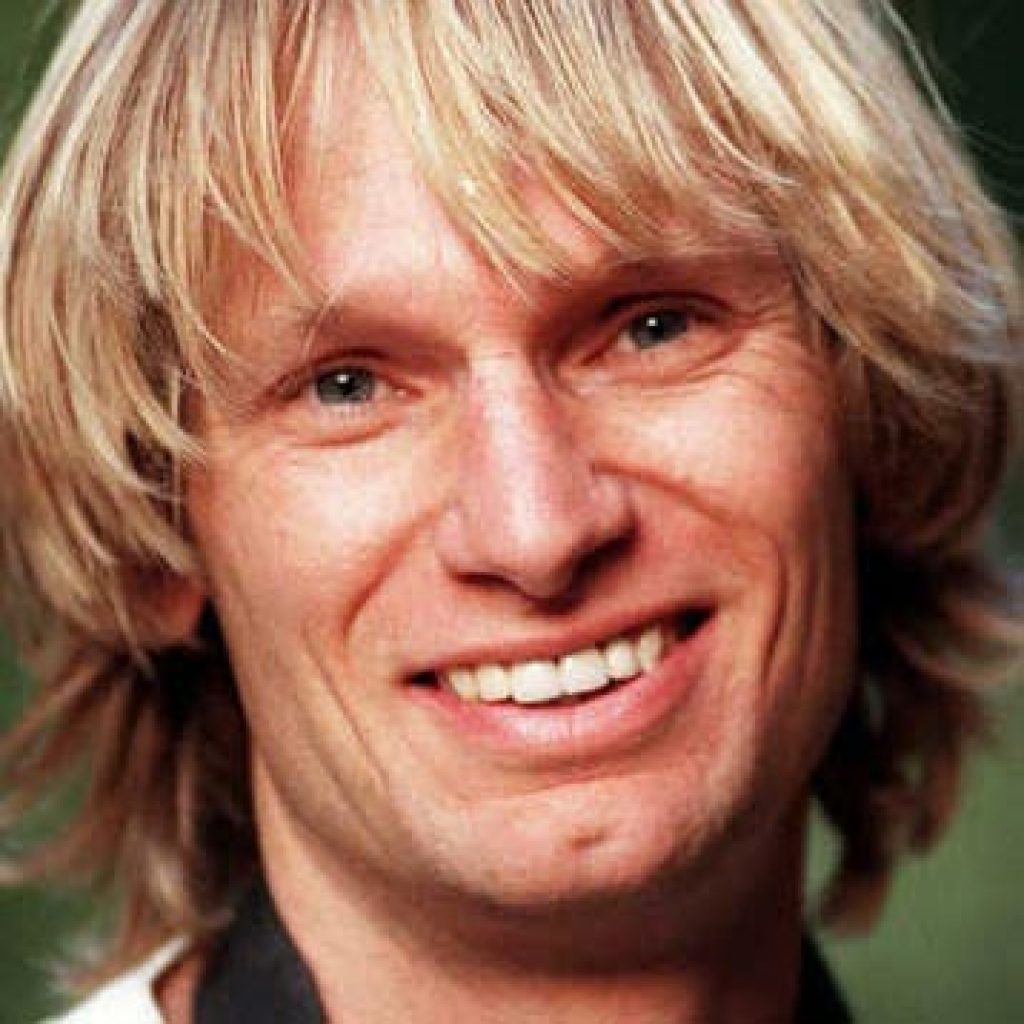

Story by Jon Bowermaster | Photographs by Barry Tessman

A five-week long journey – from California, through British Columbia and Alaska – delivered us to one of the loneliest and least known spots on Earth (halfway between Russia and Alaska), where the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea collide at what the Aleuts called the ‘Birthplace of the Winds.’

– JUNE 13 –

SAMALGA PASS, BERING SEA, DAY 1

T

he 38-foot “Miss Pepper,” out of Dutch Harbor, Alaska, shimmies violently as it plows through 12-foot seas. Peering out darkened windows all I can see are black, ominous waves meeting black, ominous skies. Our 22-foot-long fiberglass kayaks bang atop the boat’s wheel house; though secured by cam-straps and rope, 12 hours of non-stop Bering Sea rocking-and-rolling threatens to set them free. It is three in the morning, and the mood inside the cabin is foreboding as we make our way at full throttle across the dangerous Samalga Pass, which separates Umnak Island from the poetically-named Islands of Four Mountains, our goal.

An hour before we’d made an apocalyptic, mid-ocean rendezvous. A 16-foot-metal skiff appeared out of the black, piloted by one Scott Kerr. A native New Yorker long married to a local Indian woman, he lives in Nikolski (pop. 26), a village on Umnak, the only town for more than 100 miles. Since none of us – including “Miss Pepper’s” skipper Don Graves — has ever been to this part of the ocean, and Kerr had, we’d made sketchy arrangements for him to guide us these last few hours through the fog and heavy seas to the best landing spot. In exchange, we’d brought him $88 worth of groceries, including a couple bags of Purina dog chow and tins of Red Man.

Though he’d met us, accompanied by a barely awake friend, Rex, neither man appeared happy to see us. They tied off their skiff behind the “Miss Pepper” and boarded, smelling of wood smoke and tobacco, rope belts laden with long knives and heavy flashlights. “What are your intentions?” Kerr kept asking as we stood in the boat’s dim light studying maps of the Islands of Four Mountains, where three teammates and I were to spend the next month kayaking and climbing. He couldn’t understand why anyone would want to go out to these remote islands, especially on a night like this.

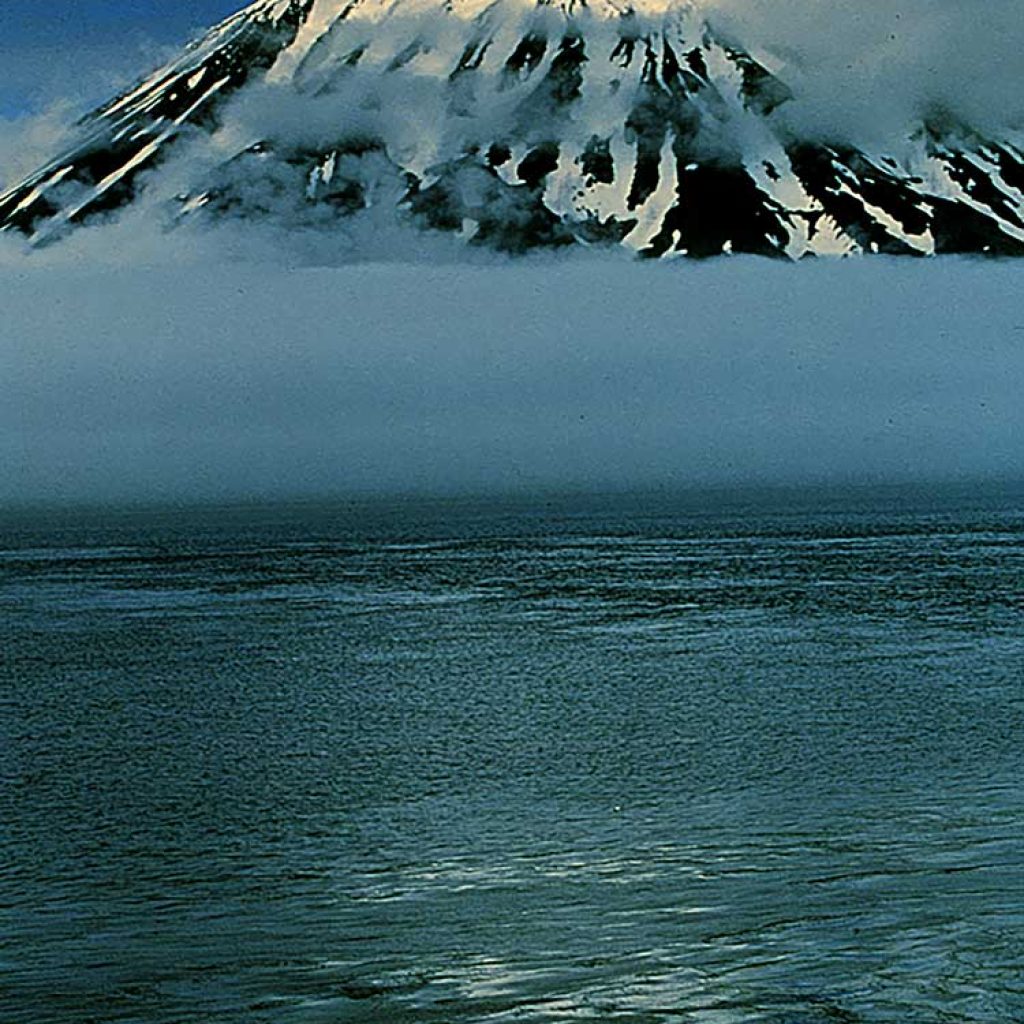

We were out here to satisfy an insatiable curiousity, a desire to test our sea kayaking skills in some of the world’s most extreme, i.e. cold and stormy, conditions. We’d first heard about the tiny group of five treeless, volcanic islands (Carlisle, Chuginadak, Herbert, Kagamil & Uliaga) buried in the center of the Aleutian Island chain, midway between Kamchatka and Alaska thanks to one of the world’s pre-eminent sea kayakers. Veteran expeditioner and author Derek Hutchinson (“Complete Book of Sea Kayaking,” “Guide to Expedition Kayaking,” etc.) tells crowds at his slide shows that the most spectacular place he’d never been but always wanted to visit was the Islands of Four Mountains. Twenty years before he’d kayaked south along the coast out of Dutch Harbor and had glimpsed the snowcapped peaks of Chuginadak and Carlisle through binoculars. Hutchinson’s expeditioning days are behind him, so we took his suggestion and ran with it.

It took me nearly a full year to raise the money and sponsorships – primarily from the National Geographic Expeditions Council and Mountain Hardwear – as well as line up the logistics required to carry us out to one of the loneliest and least-known spots on the earth. Our goal was simple: To kayak among the five islands and climb the volcanic peaks. Success was not assured, not in a place known as the “Birthplace of the Winds,” where 100-mile-plus winds are common. The channels that separate the five islands – the fast-moving waters we must kayak across – are renowned for their unpredictability. Marked by strong tides, 10-foot standing tide rips and constant winds, they are our major concern. It’s possible we’d come all this way – more than 4,000 miles — only to be pinned-down in our tents by heavy storms, unable to paddle even one mile. According to the 1964 version of the navigational guide the Coast Pilot, “No other area in the world is recognized as having worse weather in general than that which the Aleutian Islands experience.”

At 6 a.m. the motors slow, the captain studying his depth gauge carefully. “North Cove is a half-mile inland,” he pronounces, “and I can’t get any closer. I’m dropping anchor.” We are just off Kagamil Island, an uninhabited and little-known volcanic peak rising straight out of the Bering Sea, from which we would begin our exploration.

Downloading was as ominous as the run out. Barely awake ourselves, a tad green from the rough ride, we –Barry Tessman, Sean Farrell, Scott McGuire and myself – hustle to throw our heavy bags of food and gear into Kerr’s metal boat for the ride to shore and unlash our kayaks. Within short minutes, things fall apart badly: The too-heavily loaded skiff is swamped and nearly sinks in the surf piling onto the sand beach. One of the blue, fiberglass hatch covers on our Necky kayaks had come untied during the night and blows into the 38-degree ocean, sinking out of sight, despite the effort of Sean, who dives in fully-clothed to try and save it. When the “Miss Pepper”, trailing the banged-up metal skiff, finally motors away two-and-a-half hours later the only optimistic thing about our arrival is that the fog is so heavy the winds have calmed.

At this point what we don’t know about the Islands of Four Mountains far outweighs what we do know.

Over the course of the eight months prior to our June 14 arrival on Kagamil I had sought information from the expected sources. Alaskans, mostly. Men and women, who study the people, weather the history of this wild region. Boat captains, bush pilots, volcanists, anthropologists, and geologists. What I’d learned from them was . . . well . . . not much. Even the resident expert on the Aleutians at the Alaskan Volcano Observatory said when I reached him in Anchorage, “Call me when you get back because you’ll definitely know more about the place than we do.” One thing each person I spoke with assured me was that we were in for the trip of our lifetime . . . and that we would have our hands full.

The last people to kayak among the Islands of Four Mountains were the Aleuts, more than 200 years before. Few have visited since, in any craft. The islands remain an enigma, especially to descendants of the Aleuts, who have long-considered Kagamil to be the birthplace of their people and who for centuries buried their mummified dead in caves around the island. Often they were buried with their sophisticated skin-and-wood frame baidarkas, the forerunners of our fiberglass/kevlar/carbon fiber kayaks.

One man I’d been trying to track down for months finally met me at the dock in Dutch Harbor minutes before we were to pull away. Ten years before Bob Adams had motored to the Four Mountain’s to pick up an archeological team. He had nothing but good, if cautious words. “Because of the Aleut’s history, it is a very mysterious, magical place. At one time there were lots and lots of Aleuts living there. What happened to them? Where did they go? Even the Aleuts don’t have any clear idea. But when you’re out there it feels very different, more spiritual, than any other place in the Aleutian chain.”

“Because of the Aleut’s history, it is a very mysterious, magical place. At one time there were lots and lots of Aleuts living there. What happened to them? Where did they go? Even the Aleuts don’t have any clear idea. But when you’re out there it feels very different, more spiritual, than any other place in the Aleutian chain.”

– Ferry Boat Captain

– JUNE 15 –

NORTH COVE, KAGAMIL ISLAND, DAY 2

T

his is expeditionary paddling at its utmost. Simply making the crossings in our heavily loaded boats is our first and major concern. Unlike a big mountaineering trip — with the accompanying Sherpas and literally tons of gear — we will have no base camp. Four of us in two big boats will carry everything we need – food, fuel, paddling and climbing gear, emergency and first aid equipment, a small mountain of camera gear – for five weeks. We can’t risk leaving any necessary food and gear behind in case one of those fabled Aleutian storms comes out of nowhere and we’re not able to get back to “base,” thus separating us from our lifeline for a week or more.

Our first test is today, when we attempt the short – 2.5 miles as the crow flies, which means we’ll sprint for more like 4 miles – crossing from Kagamil to little Uliaga, the northernmost island of the group. Through binoculars we can make out a rocky beach on the eastern edge of Uliaga where we’ll be able to pull up the boats for a daylong exploration of the island and its 2,500-foot volcano.

To our advantage, we have all top-of-the-line gear – light boats, super-strong paddles, and layers of fleece, neoprene and Gore-Tex. But the Bering Sea is not a place you want to spend anytime in the water. Each morning I measure the temperature of the ocean; it runs between 35 and 38 degrees. Air temperature averages in the low 40s, with wind chill in the mid-20s. Not exactly the best swimming weather. In practice these big boats, weighing between 700 and 800 pounds when loaded, could be rolled back up if we were overturned. But the reality is that if the boats are dumped, we’ll most likely end up swimming. If that happens it will be essential for us to get back in the boats in less than five minutes before hypothermia begins to slow our hearts. It’s said that the most-fit Aleut kayakers could survive 45 minutes in these waters; I give us 15 at the outside. We wear locator strobe lights on our PFDs and each boat carries an emergency beacon, which we jokingly dub “cadaver finders.” Any rescue would come out of Dutch Harbor, 150 miles away. By the time our distress signal was picked up, we would already be dead.

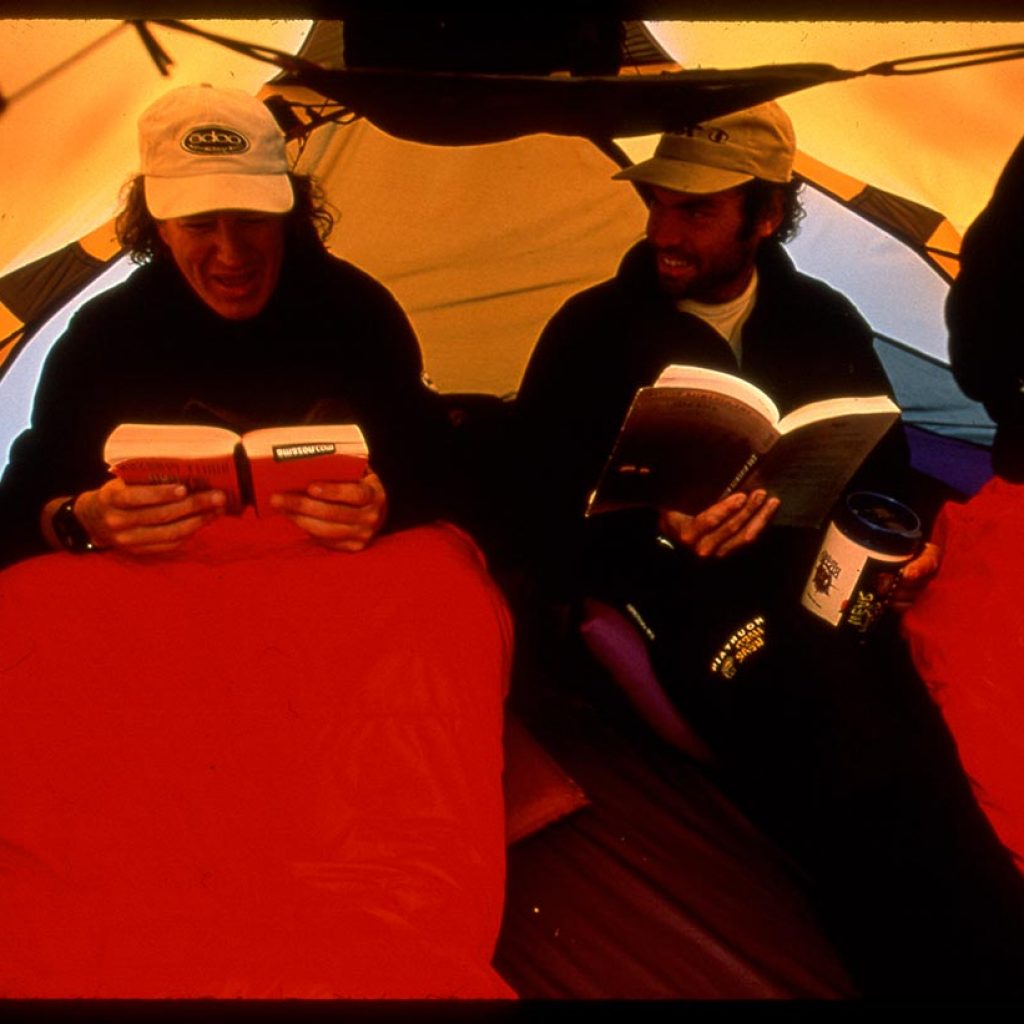

Another plus is that we are a strong team: Barry, 39, makes his living as a photographer but in past lives has been a raft, ski and kayak guide. Scott, 27, tall and rangy, is an ambitious, experienced sea kayaker. Both are like human motors in the back of the kayaks. Sean, 31, a lawyer with Orange County’s biggest firm, has sailed around the world using only a sextant; his navigational skills are key since we hope to do the bulk of our paddling in foggy, thus less windy, conditions.

As we push off the beach for our initial foray, I’m nervous. Socked in by fog, the land behind us is swallowed within minutes while the small island to our north is invisible. In rhythm, we cut through the fog, the current crossing our bow at a fast 5 to 7 knots, skirting whitecaps marking a long line of tidal rips. Bands of puffins and murres fly hauntingly out of the fog overhead. After 30 minutes of sprinting the greening meadows of Uliaga emerge. We debate whether to fight the current west to a small beach we can see, or paddle east around a corner where we know there are sizable tide rips, but also a pair of round-rock beaches. My left arm is completely exhausted due to the shot-from-a-rocket sprint pace we must keep. This is not Baja, no place for leisurely paddling. “Paddle for your life,” is our motto.

Changing out of drysuits we climb a steep, grassy cliff emerging onto a large, sloping green-brown meadow just beginning to bloom with buttercups, marigolds and Nootka lupines. The skies had cleared and we’re afforded a magnificent view back at Kagamil’s dormant volcano. During the next hour we’ll be able to see the faint outline of the 5,600 foot volcano on Carlisle and hints of the two big volcanoes on Chuginadak.

Our day-hike takes us high to meadow lakes and patches of snow. We rest at 1,500 feet and watch a band of bald eagles soaring overhead.

Back on the Bering Sea – at 7 p.m., slack tide — we hope to catch the wind out of the northeast to help blow us back towards North Cove. We paddle far out to sea to miss the big whitecaps just offshore marking tide rips, plowing through four foot swells. Swamping waves out of the west completely submerge our 22-foot-long boat. “Now you see ‘em, now you don’t,” Scott yells as we watch the other kayak disappear into deep troughs of coal black sea.

Our return is capped by a dramatic surf landing, the boats propelled into shore by pounding six-foot waves. As we pull the boats up onto the inky sand beach it is with noticeable relief. The first two crossings are behind us.

– JUNE 16 –

NORTH COVE, KAGAMIL ISLAND, DAY 3

S

even p.m. We’d hoped to leave for the south end of Kagamil today. Instead, we’re back inside our hastily re-set tents. Outside the sea is banging, the wind moaning. Big gusts roaring in from the ocean meet another set hammering down the hills behind our camp. The encounter flattens our tents, which resiliently keep popping back up.

Not paddling was definitely the best call. Among everything we carried with us out here patience may prove to be our most valuable asset.

The plan had been to leave the beach at 11 this morning, round Candlestick Point, then slide down the west edge of the island, staying within 200 feet of the shoreline. We guessed it could take three to four hours in our heavily loaded boats.

As we loaded the boats, the winds had picked up. Scott and I kept an eye on the pass separating Kagamil and Uliaga. With the naked eye we could see whitecaps growing. What we could not see, and could not predict, was what the seas and winds were doing around Candlestick Point. Our concern was that we would round the point, start heading south, only to find conditions raging, with the fierce wind blowing in our face or out to sea. If forced to retreat, our heavy boats might work against us and we might end up spending the night afloat in them, or pummeled against tall cliffs. Our next possible camp was more than eight miles away.

“I think we’ve missed our window of opportunity,” an impatient Scott said to me as we watched an offshore williwaw whip up a quarter-mile long horizontal band of sea spray.

“The window has actually just been slammed shut,” I suggest a few minutes later when a gust nearly picks up our loaded kayak. It is bleak, wind-whipped and cold out there, a frosty, smoky cauldron of nasty seas.

Presented with the notion of resetting camp, Barry and Sean concur. This is our first glimpse of real Aleutian weather, our first opportunity to make a decision about whether to stay or go. We choose on the side of caution.

“Good call,” says Barry as we watch williwaw after williwaw chase one another through the pass, a cold rain pouring from the skies.

– JUNE 19 –

NORTH COVE, KAGAMIL ISLAND, DAY 6

W

e finally made it to the south end of Kagamil yesterday, under sunny, blue skies. We lolled on the rocks in T-shirts as we unloaded the boats and dried all of our gear. Now, 24 hours later, we’ve climbed to 2,500 feet – 419 feet below the volcano’s summit – and are being buffeted by 40-mph gusts. Sleet and loose rock (a softball-sized chunk misses Barry’s head by a few feet as we near the summit) make climbing treacherous. The brown fog and noxious smells emanating from dozens of sulfur vents make it seem otherworldly.

We opt not to go for the summit due to the loose scree and dangerous rock. “This is no place to take a digger diving out of the way, or a rock to the head,” concludes Sean, our most experienced climber, pointing to the numerous slides and rock falls all around.

These conditions make us very concerned about our chances of summiting the big volcanoes on Chuginadak and Carlisle, each rising nearly 6,000 feet straight out of the sea. Twice as high, covered with up to 100 feet of snow, they are far steeper. Will we be able to get up them? Here, this day, with winds gusting upwards of 40 mph, it’s a worry.

As we descend, the steep valley that spreads before us affords haunting views along the flat, green coastline. We are constantly on the lookout for signs of the Aleuts who lived on these islands as far back as 8,500 years ago.

“How about those flats over there,” points Barry as we crest a small ridge. “A perfect place for an Aleut subdivision, the perfect place to hide from the winds.”

The Aleutian chain was once home to 15,000 to 25,000 Unangan people, who lived in villages of sod-covered houses, built in protected coves along the seacoast. They survived on marine life and sea mammals, bird eggs and plants. When the Russians arrived in the mid-1700s, they renamed them the Aleuts and brought them epidemics, violence, starvation and slavery. By the early 1800s, the Native population had dropped to less than 1,000. Today just a handful of the 150 islands have any human population.

On our way back to camp we hike to the southeast corner of the island, where Scott Kerr had said we’d find the site of a thousands-year-old Aleut homestead known as the “Village Where it is Always Warm.” Sulfuric vents had cooked the surrounding ground red and raw, moonscape-like. In many places we think we can make out traces of centuries old barbaras, the communal cave-homes where the Aleuts lived. We find thick, tablet-like rocks sticking straight up-and-down in the tundra, potential cairns for the sea-faring Aleut fishermen. Around every turn in the tundra we were sure we’d found a new cave, blocked by giant stones, possibly, hiding undiscovered mummies.

The largest collection of mummies in the Aleutians – a burial habit going back 3,500 years and most likely introduced by nomads from Egypt – was found in caves on Kagamil, near where we walk. The bodies were carefully eviscerated, stuffed with wild rye and placed in a sitting position, knees drawn up under the chin, arms folded, head bent forward. The natural heat of the volcano dried and preserved them; landslides and geologic disturbances sealed the entrances to many of the caves and locked away their secrets forever. Discovery of the mummies –by Russian explorers, American fur traders, Smithsonian archeologists – helped to build the enigmatic mystery of the Islands of Four Mountains.

– JUNE 21 –

NORTH COVE, KAGAMIL ISLAND, DAY 8

T

he morning dawned thick with fog. We could not see the cove we knew was 100 feet below our camp. Air temps were below freezing. What we expect to be our most difficult crossing will be tried today, the longest of the year.

The conditions bring a knot to my throat, which I guess is my heart. Yesterday we’d scoped out the near-cliffs of Chuginadak through binoculars, mapping a hoped-for crossing route. We’d been able to make out a big waterfall in the center of the opposite cliff wall, our target.

As we broke camp, packed and slid everything down the steep hill of wet grass and mud to the rocky beach below, it was with no small weight of anxiety. If we got out there and the currents or winds were too strong for us to beat into, we would be in serious trouble, paddling for our lives, next stop — depending on the wind direction — the North Pole, Hawaii, Kamchatka or British Columbia.

Packed and loaded by noon we pushed off just as high tide was peaking. The plan was to paddle to the steam jets at Kagamil’s southern point — the closest point of land to Chuginadak — then sprint like mad, most likely ferrying into the wind to take advantage of any current that might help push us towards landfall. But, with Barry and Sean out front, as soon as we cleared the first point of land, the sprint began. The gut decision had been made without consultation to just go for it, straight across the pass.

By the time Kagamil disappeared in the fog behind us – with Chuginadak still buried somewhere in front – the sea was a cold mish-mash soup. Wind-churned four-foot swells crashed over the starboard; Scott struggled to keep the boat on course. One hundred feet ahead of us Barry and Sean zigzagged, attempting to match compass readings to conditions.

Within 20 minutes my bare right hand was numb; every time I paddled on my right side, thanks to the swells, it took a dipping. At the same time I was over-shifting my bodyweight to the left in order to try and get a stronger pull on my weak side, forcing Scott to overcompensate by throwing his body weight to the right. “When you paddle on your left, lean hard on your right butt cheek,” he screamed over the wind.

Every time we ventured onto the sea I flashed to what it must have been like for the Aleuts who refined travel by kayak and created the shape of the boats we are paddling.

The Aleut word for the craft was ikyak; the Russian’s who introduced the better-known baidarka. A village’s, and individuals, strength was often expressed in the number of kayaks they owned. Their relationship with the sea shaped the Aleut’s psychology, quickened their minds, and exterminated incompetents. Their relationship with their boats was so intense that over generations they became shaped to the demand of kayaking vast distances, developing huge upper bodies from relentless paddling and bowed legs that allowed them to sit confined for hours. Kayak hunting on the open sea – the Aleuts primary form of subsistence – is perhaps the most skilled and demanding form of hunting practiced by man.

(The Aleuts relationship with their boats was not without some oddity. If a man in the polygamous society slept with a woman he was obliged to share his affections with the kayak. If he did not, it was believed, the boat would become jealous, break and not return the hunter to his village. The result was an elaborate session of rubbing the kayak in the morning before going out to sea …)

Those early boats were extremely sophisticated. The cover was made from sea lion skins, pulled over a frame of whalebones tied together with baleen and hinges carved from polished ivory or bone. As many as sixty small animal bones were strategically inserted into the framework as joints so that every part of the ikyak was in motion as it moved across the sea. They carved double-bladed paddles (similar in shape to the ones we are using), and wore a sealskin shirt that fitted over the cockpit to keep out water (exactly like the neoprene-and-kevlar devices we wear). Superior celestial navigation skills allowed the Aleuts to travel hundreds, even thousands of miles across open water to destinations now named Barrow and Hawaii. The best of them could sustain 10 miles an hour on the open ocean, in boats ranging from 15 to 30 feet long. Many were lost at sea and even the best hunter-kayakers were sometimes overturned. Most often they went out with a partner, so they at if one boat flipped he could be pulled to shore by his friend. If caught in open sea by williwaw or long storm, several hunters would lash their boats together to ride out the storm.

After sprinting for an hour, it looked like we might not reach Chuginadak for another hour. My arms were tired, feet numb. Two orange-hooded paddlers bobbed in and out of troughs just ahead.

“How’s the weather,” I shout to Barry as we pull alongside for a mid-pass conference.

“Dangerous,” was the response

– JUNE 23 –

SKIFF COVE, CHUGINADAK ISLAND, DAY 10

A

t 8:16 p.m. yesterday we witnessed something we hadn’t in three weeks.

The wind died. Completely.

Just like that, out came the gnats and up came the putrid smell of sea kelp at low tide. The air was alive with the sounds of birds and the wash of sea on rocks. We moved outside of our tents, which had stopped flapping, and no longer had to shout to be heard. Hats off, jackets unzipped, the temperature climbed to 52 degrees.

It lasted for an hour, and we all agreed it felt wrong. The Aleutians without wind are not the Aleutians anymore.

We should have guessed the wind’s disappearing act was not a particularly good sign.

The storm began at three in the morning, with a ferocity we’d not yet seen. Rains dumped and 35 mph gusts of wind pounded down on the tent walls like a heavyweight’s fist. During the night the wind sounded like a busy carpenter’s shop, sawing, hammering and drilling on our thin nylon membrane of protection. Instinctively we leaned shoulders and palms to the sides and ceiling of the tent.

Emerging mid-morning required full-on rain gear. The cove in front of us was whipped blue-gray with whitecaps. Beyond, in the pass, we could see monstrous waves churned by a wind hard from the east. All the beautiful waterfalls we’d seen the day before surrounding our camp were being blown horizontally, forced back up over the cliffs.

Late in the afternoon Sean – restless, curious — pounded on our tent wall. Suffering from tent fever he’d taken a big hike despite the wet and cold. He was reporting that he’d discovered a downed World War II fighter plane.

Putting on four layers, including Gore-tex pants, jacket and mittens, we piled out of the tents to retrace his path up the hills, over ridges and fast-running streams. We hiked into 45-mph winds, which nearly blew us over backwards. The temperature was eight degrees.

At first, Sean thought he’d discovered a beached whale high on the hill; without his binoculars he had to get close to realize it was a plane. Upside down, its two-passenger cockpit smashed into the spongy moss, a single rubber-landing wheel spun in the wind. A metal catch-hook indicated it had come off a ship. The propeller and one wing were thrown to the side. Unexploded ordnance lay half-buried in the grass. The ID on its fuselage indicated it had last been serviced in September 1943, on Kodiak Island.

The history of the Japanese invasion of the Aleutians is a little-known part of World War II history. For 18 months in 1942 and 1943, several of the bigger islands were occupied by Japanese troops; ultimately 1,500 American lives were lost defending the Aleutians – the only time enemy soldiers have occupied American turf — most of the deaths attributable to hypothermia and frostbite rather than enemy bullets.

– JUNE 28 –

CARLISLE COVE, CHUGINADAK ISLAND, DAY 15

W

hen the alarm went off at 6:15, I think we all quietly prayed it would rain just a little harder so that we could justify staying in our tents rather than go onto the sea in what we knew would be a 30 degree day.

Our plan was to cross from the center of Carlisle to the northwest corner of Chuginadak, about 4 miles, hopefully using the last of the early morning’s outgoing tide to help pull us across. Once there, if conditions – i.e. currents and winds – looked in our favor, we would then attempt the 4.5 mile crossing of Chuginadak Pass, the most unpredictable and dangerous of them all. If wind and current were sweeping too hard, we risked being carried with it, past the southernmost point of Herbert, next stop Kamchatka.

We had somewhat heatedly debated the crossing plan for many hours yesterday. Timing was the issue. Scott wanted to leave early, before the flooding tide was exhausted, in order to take advantage of its tow. The argument against leaving too early was that we didn’t want to be sucked out-of-control into what we knew was a dangerous current running between Herbert and Chuginadak islands without at least the option of pulling into Chuginadak.

The temperature was 34 degrees as we loaded the boats. The drizzle was nearly snow. Dressed to thrill in Polar fleece 200 one-piece suits, Goretex dry suits, Goretex Skanoraks, three layers of fleece-and-neoprene socks and booties, fleece-lined skullcaps and Pogies, we pushed off a minute before 10 o’clock.

We caught the fast-moving tide just past the edge of the kelp bed and took off like kayak-rockets. Forty-five minutes later we had cleared the strong current and reached flat water a quarter-mile off Chuginadak. From sea level we now needed to gauge the speed of the current separating us from Herbert and assess if we could sprint across it.

From our boats we scouted a couple rocky beaches on Chuginadak as potential retreat points should we venture out and find the currents too strong. We then paddled due west, still riding a piece of the outgoing tide. We were heading to the swirling edge of the choppy current, which was heading east and north – neither a direction we wanted to go. It promised to be a fast, bumpy, swamping ride, demanding a lot of Barry and Scott who manned the rudders to keep us on a direct course amidst all the sea-rubble.

Cold was definitely a factor. Inside our drysuits we were perspiring but hands and feet were frozen. The way we must load the boats when leaving rocky shores – requiring us to stand in the water for 15, 20 minutes – insures that from the very start of the day, our feet are numb.

Midway across the channel, which sounded and moved like a roaring river, and despite the mish-mash of waves swamping fore and aft, it was apparent that we’d at least reach Herbert’s shore. We paddled the two boats close together and tried to pick a landmark.

“How about that ‘V’ to our right,” shouted Barry.

“Or that washed out cliff further south,” I yell back. We decided on a rocky spit we could just make out between the two sites and picked up the paddling pace.

When we hit the kelp line, suggesting we were out of the big currents and wind, I breathed a sigh. Herbert was our 5th of five islands. Though only a modified success – we still had to get back to Chuginadak to make our pre-arranged pick-up – we had achieved one thing we’d set out to do, put our feet on each of the islands.

As we pulled the boat’s onto yet another rocky beach, Barry shared with me the sizable concern he’d had mid-crossing. “We were boomeranged, nearly out-of-control, across the channel, through tide rips. If we hadn’t made that eddy at the corner of Chuginadak, then where would we have ended up? That was definitely our most sketchy crossing.”

– JUNE 29 –

HERBERT ISLAND, DAY 16

R

ain continued through the day, stopping just before midnight, when skies cleared and a haunting light emerged from behind the clouds. It was the first night of the full moon.

We gathered outside our tents. Mt. Cleveland peered over our left shoulder, Herbert’s volcano rose straight above us. As we watched from our high-meadow camp, the clouds moved away, exposing the moon in its perfect roundness. It lasted long past midnight, a perfect birthday gift (my 45th) from the Aleuts.

What surprised me most out here has been the spectacular beauty. We anticipated only cold and rain and fog. We’ve had that, certainly, but we’ve also seen incredible blue skies and billowing white cumulus. We’d had afternoons when sunlight dappled the green coastline and hints of the magnificent, sun-slashed volcanoes peaked through the clouds. Even the fog has not always been gray; like window blinds, it lifts and opens, allowing just enough sunlight through to set the landscape aglow.

– JULY 1 –

HERBERT ISLAND, DAY 18

I

f we’d known the seas we were in for today we probably wouldn’t have paddled.

Maybe we’d grown a little over-confident. We’d been out here nearly three weeks and had made six successful crossings. Despite the wind and rain and roar of the sea this day we barely thought twice about whether to go or not. This was exactly the kind of day where plenty could go wrong.

With both boats in the water, as soon as we broke from the protected lee the winds and current began hammering us.

“Mach I,” shouted Scott from behind me. Thanks to the wind I could barely hear him.

We were heading straight across to Chuginadak, four miles as the crow flies. It would be tough to hold a true line, with strong winds and stronger current sweeping from the south.

By the middle of the pass it was apparent we’d bitten off a big day. Four-foot swells marched north, forcing us to paddle hard at an angle across the waves, then try to position the boat facing directly into them. One result was that we were constantly awash in icy saltwater.

Mid-pass I unleashed the wind meter from beneath the bungee cord in front of me. It registered gusts of 20 mph, wind chill a cool 26 degrees. Peaking over my shoulder I kept lookout for sight of the two orange Skanoraks Barry and Sean wore; if I could see them that meant their boat was still upright.

As we pulled within one-and-a-half-miles of the towering Mt. Cleveland a fierce wind greeted us head-on, racing down the volcano’s 6,000-foot slope to crosshatch the sea. Now, even as we were swamped from the south, the boat pitch-poling into three and four foot waves, we had to pick up the pace as we paddled into the wind.

When we finally turned the corner around Chuginadak, we were still nine miles from Applegate Cove. There was a bit of a head wind and we were paddling into current, but it wasn’t too bad. The sun had come out – though behind us Herbert was completely socked-in by fog and rain – and the big volcanoes were beautifully exposed under blue skies. Our 7th and final crossing was completed and it felt good to be coasting down the final stretch.

Hah!

Just as we breached the last rocky pinnacle jutting into the sea, anxious to lay eyes on Applegate’s black sand beach, a riotous 30 mph wind smacked us starboard. Roaring through the slot separating Chuginadak’s twin volcanoes these were strong Pacific Ocean winds literally roaring through the slot carved in the island by centuries worth of conditions exactly like this.

Like that, we were surrounded by whitecaps. When I picked my paddle out of the water, the wind almost ripping it from my hands. Forward progress was nearly impossible. The bow dug into the waves at an angle and each time it did I got a face full of cold saltwater; simultaneously, every time I lifted my right paddle out of the water, the wind carried its load directly into Scott’s’ face.

Shouting at the top of my lungs I suggested taking refuge in the nearby kelp pads, like seals do during storms, to sit and see if the winds might die.

Scott shouted back, “No way, it could get worse before it gets better and then we’d be stuck here for the night. Let’s keep paddling.” Barry had chosen a route a mile out to sea, trying to avoid the wind’s ferocity. “I don’t like what they’re doing, “ Scott shouted, “if they get blown out, they‘ll be in the middle of the pass within minutes. We want to stay close to shore in case it really goes off. “

We’d already paddled a hard 10 miles and paddling into the winds made these last miles even tougher. There were times when I thought we’d be blown back to shore, or worse, out to sea. When we reached the heart of the slot the wind picked up again, grew stronger. We could see the canyon the wind roared through. It was black, filled with fog and cloud, like some kind of sub-Arctic hell.

– JULY 4 –

APPLEGATE COVE, CHUGINADAK ISLAND, DAY 21

A

t 7:04 a.m. on 7.04.99, temperature 26 degrees, we headed from camp for the peak of Mt. Cleveland. In a direct line it was roughly a 10 mile trudge each way, straight up 6,000 feet. Sean estimated it would take us 12 to 15 hours to make the round-trip.

Cleveland is one of 57 active volcanoes in the Aleutians and has erupted more than a dozen times since 1893. The last was on May 25, 1994, when it sent a plume of ash six miles into the sky. The mountain is porous and hot; thus we expected the snow to be soft. We’d come prepared, with crampons, ice axes, harnesses and ropes, but we’re concerned we might near the top and find ourselves thwarted by soft, deep snow and the steepness of the peak.

If there was some kind of Aleutian god smiling down on us, he/she continued. Ever since we left Herbert it’s been buried in fog and rain; if we hadn’t left there when we did, we’d still be stuck. Today, the day we chose out of the blue – Why not climb the tallest peak on the 4th of July? – the weather couldn’t have been more accommodating.

Two thousand feet up we stop to put on crampons and harnesses. Looking out over the Bering Sea, Uliaga and Kagamil are perfectly exposed. We can see distinctly the routes we took between the islands, even the coves where we made camp and the nasty tidal rips we skirted. The view also afforded us a glimpse of what early sailors saw as they passed by to the south – the volcanic peaks of Herbert, Carlisle and two on Chuginadak – thus, the Islands of Four Mountains. (Kagamil and Uliaga would have been hidden from their view . . ..)

It is a steep climb across predictably soft and deep snow. We stick to the widest, snowiest shaft, traversing the mountain north to south and back again, slowly gaining altitude. A slip would result in a fast glissade on slick snow until you were ripped to pieces at the bottom by the sharp, black lava rock. Ironically, the only death-by-volcano in the Aleutians occurred on this mountain. In 1944 a two-day eruption, mirrored with severe earthquakes, sent lava pouring three miles down its slopes. An American soldier, part of a small Air Force radio team stationed on the island, got too close to a vent and was killed by a mudslide.

“It’s unbelievable,” I say, motioning with my hands, “from here it all seems so . . . peaceful.”

As we ascend the wind picks up, whistling downhill, dry snow ricocheting off our hoods. Stopping to pull on snow pants and another layer of fleece, we hack a ledge into the snow with boots and axes. The view out over the Bering Sea remains magnificent, blue and clear. We hoped conditions would hold long enough for us to see Carlisle and Herbert as clearly. Balanced precariously on the ledge, 40-mph wind gusts rachet up and within seconds we are enveloped in a snow hurricane and everything around us – crampon bags, photo gear, bags of nuts, axes — is buried. As quickly as it arrived, it subsides. (One thing we’ve not seen much of these past three weeks? Man. In nearly a month we’ve glimpsed a solitary tanker on the far horizon, heard a small plane in the clouds, and, from Herbert, watched an oil company helicopter buzz Mt. Cleveland.)

The next thousand feet are far steeper. We can’t make out the peak above us, but finally at 5,100 feet we reach a north-facing corner and there’s Carlisle Island, rising like an upside down ice cream cone out of the sea, rimmed by a skirt of emerald green meadows. Barry and I sneak out to the edge for a clear view from west to east.

“It’s unbelievable,” I say, motioning with my hands, “from here it all seems so . . . peaceful.”

The next traverse takes us past a small, smoking crater just off-peak, then leads to a jumble of sharp and jagged lava rock that rims the peak. We sit to take off our crampons, the summit just 50 feet above us.

Scaling those final 50 feet may have been the hardest work of the day, requiring us to literally crawl over the loose scree, difficult to stand due to the violent winds. Once on the summit, Herbert and its distinctive blown-in-half volcano were as clear as the others. I fish out my wind-meter and brace myself into the blow: 51 mph, wind chill 2 degrees. Struggling to stand, we turn 360 degrees before dropping to our knees to peer over the edge of the caldera, into the heart of the volcano, an oblong hole, bubbling and yellow, surrounded by several hellish vents leaking poisonous smoke from deep down under.

We shout congratulations and trade positions so that we can see all of the views. I sit, my back against a jagged, tawny-colored rock and try to take in everything in front of me, and rewind through all we’d experienced these last weeks.

Given the day – the 4th of July – I made a small toast, with a thermos-cup of hot Gatorade, to a single sentiment. To something that helped propel us out to the middle of the Bering Sea, across the channels, up this mountain and to whatever place will next capture our insatiable curiosities. “To Independence,” I said quietly.

– EPILOGUE –

Twenty-five days after the “Miss Pepper” dropped us off, it returned – loaded with shower water, thick steaks and beer – and plucked us off Applegate Cove.

As a result of reports I made during the trip on National Geographic’s website, the Department of Defense heard about our discovery of the World War II plane and within a month had dispatched a pair of specialists to check it out. Though they made it to Chuginadak, the terrain and deteriorating weather conditions prevented them from finding the plane.

– CREDITS –

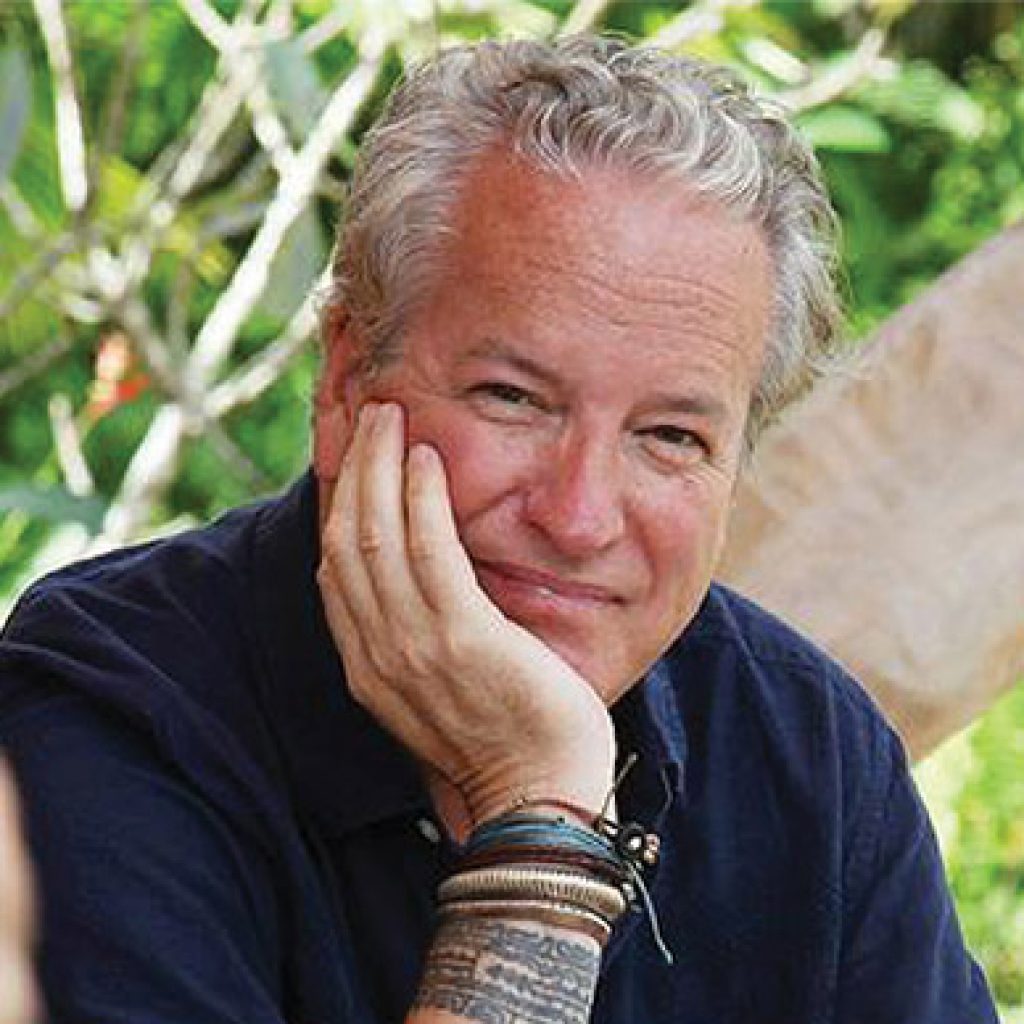

Writer, filmmaker and adventurer, Jon is a six-time grantee of the National Geographic Expeditions Council. One of the Society’s ‘Ocean Heroes,’ his first assignment for National Geographic Magazine was documenting a 3,741 mile crossing of Antarctica by dogsled. Jon has written a dozen books and produced/directed more than fifteen documentary films.

Scott McGuire has been a leading executive and designer in the outdoor industry ever since our Aleutian Island adventure.

Sean Farrell is still the most adventurous attorney in Orange County and we have sailed twice to Antarctica together to kayak.