DESCENDING THE DRAGON

VIETNAM

Story by Jon Bowermaster | Photographs by Rob Howard

My initial request to bring kayaks to Vietnam was greeted by the government in Hanoi with five simple words: ‘That will be quite impossible.’ Unprecedented, unnecessary, unsafe, unwise, he continued. More than a year of negotiating followed, as well as a cash imbursement (‘filming permit’), before I was allowed to ship the kayaks and apply for visas for a five-person team.

oken this morning by a symphony of Hanoi street sounds rushing in over my balcony . . . the first bleats of the army of motos that propel the city, the gentle cry of a local Jimi Hendrix soaring out of an alley near Hoan Kiem Lake, the scrape of metal grates being pulled back from storefronts. While charmed by these early urban echoes I am ready to be on the sea, the South China Sea to be exact.

My initial request to bring kayaks to Vietnam had been greeted by the government man who controls visits by journalists with five simple words: “That will be quite impossible.”

“Unprecedented, unnecessary, unsafe, unwise,” he went on. It took more than a year of negotiating, plus payment of a sizable cash imbursement (“filming permit”), before I was allowed to ship the kayaks and apply for visas for a five-person team. (How sizable? I paid $200 a day in a country where the average annual wage is $211 . . . .)

My goal was straightforward: To kayak the coastline from near Mong Cai on the China border to Hoi An, just south of Danang. It would take about six weeks; one reason the government was against the idea is that no one had ever asked permission for such before, they said they were concerned about our safety and worried that we might compromise certain “military sensitivities” as we descended the coastline.

I was drawn to Vietnam by just how little I knew about life here post-1975. I was curious about the geography, the land, the environment, and we would see a wide cross-section, from the limestone islands of HaLong Bay, to jungles running right down to the sea, to wide sandy beaches south of Danang.

But mostly I wanted to meet its people. One-third of Vietnam’s 80 million live on or near the coastline. Until 9/11 the people we’d be meeting were our last, great enemy, clad in black pajamas rather than turbans, hiding in swamps not caves. The kayaks would allow us to approach from the sea, hopefully connecting us in a way different than if we had arrived overland, more as equals than as visitors, our boats serving as floating ambassadors in a country where just 30 years before we would have been seen as targets rather than friends.

Daybreak, Tu Long Bai, 100 miles south of the Chinese border, the beginning. During the night a dense fog set in over the haystack-shaped limestone islands that line the coast of northern Vietnam. On the junk’s roof, just beyond its rolled burgundy sails where I slept beneath the stars, four shiny kayaks sweat under a morning dew.

A silvery morning dawns as the fog slowly lifts, unveiling layers of the tree-covered stone islands. The clearing is accompanied by the sounds of songbirds, howler monkeys and the incessant putt-putt of the two-stroke engines that are the lifeblood of these fishing people. We are camped next to a small floating village – plywood-and-2×4 houses built on Styrofoam floats – and mom’s cooing to an infant, dad’s striking a hammer and dogs barking, all echo off the tall walls that surround.

We slip the kayaks onto the glassy, green sea. These 3,500 limestone islands are probably the best-known geographic image the world has of Vietnam. All around are traces of the giant Descending Dragon after whom these bays are named. It is said to be his enraged thrashings that carved the canyons and hollows in the mountain landscape and allowed the surrounding seas to thunderously rise and flood them. Each fantastically balanced sandstone boulder, each submarine cave and limestone grotto shows the scale print of his writhing.

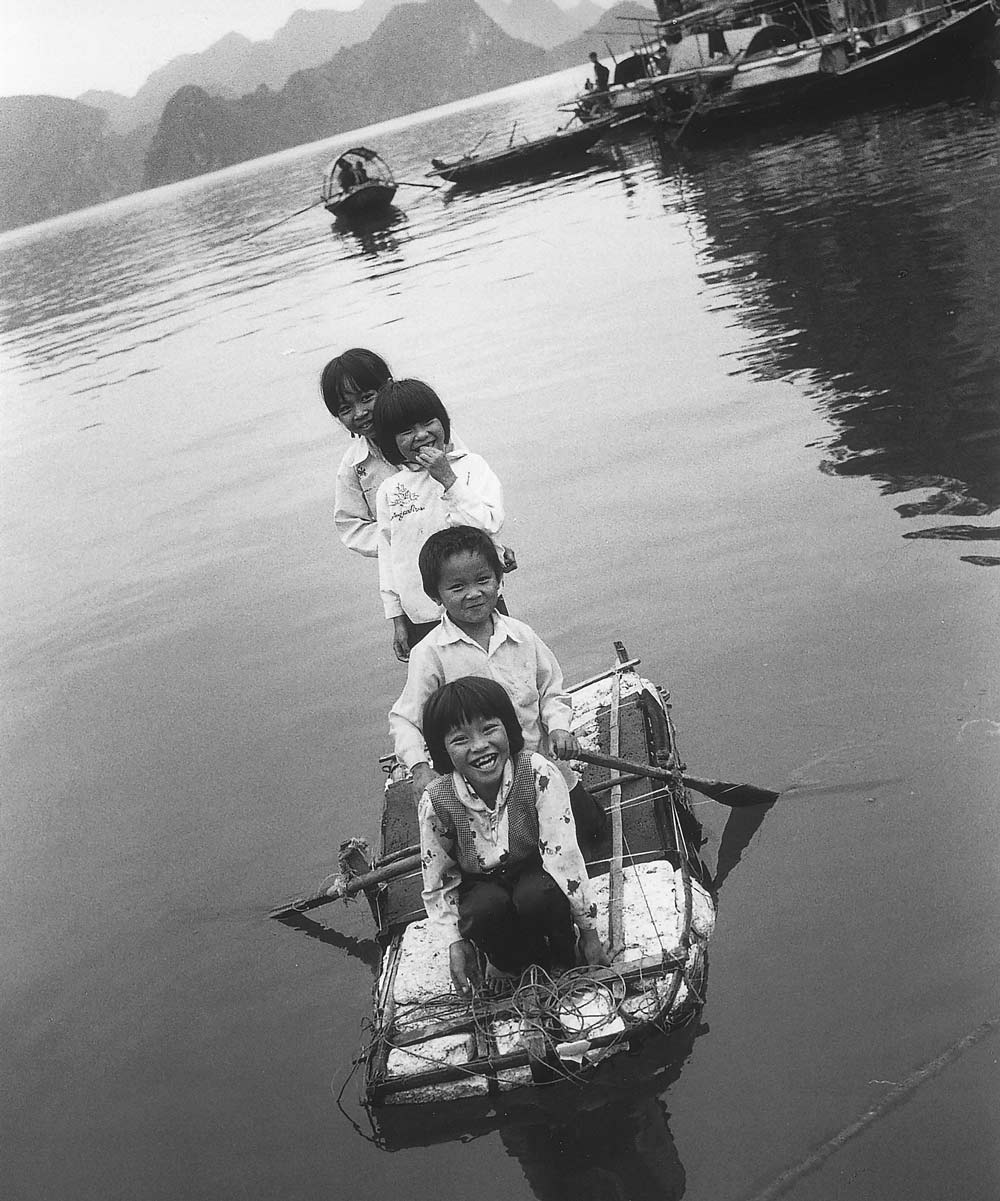

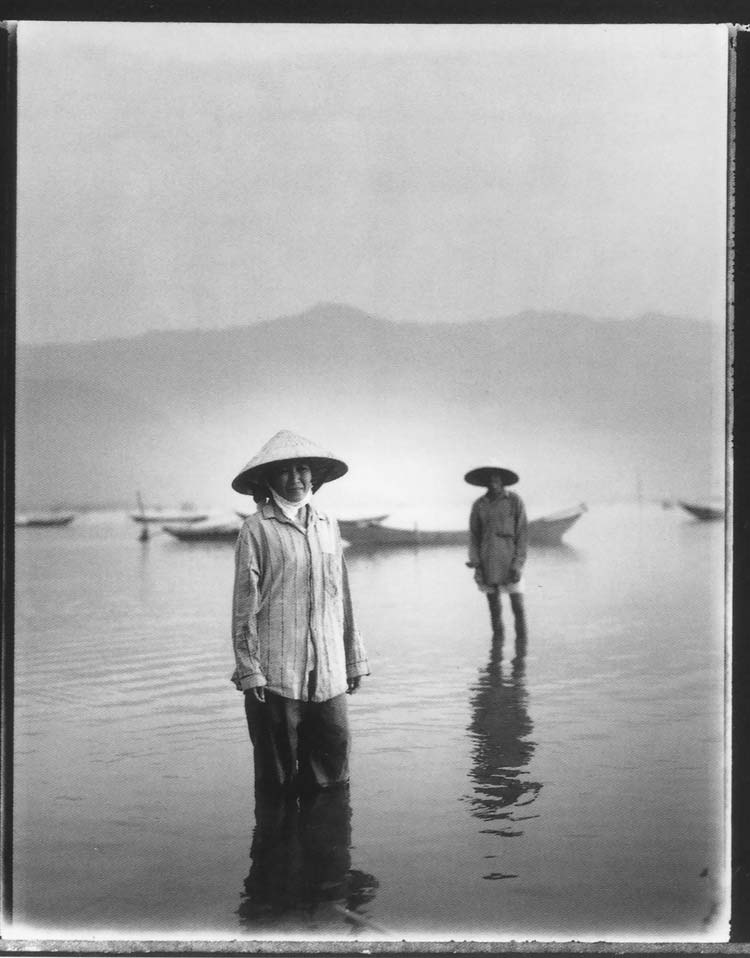

The limestone islands of Halong Bay are probably Vietnam’s most significant landscape. These women are operating what are essentially floating 7-11s, selling fresh fruits, candies, bottled water, chips to passing tourist boats and fishermen. Obviously it’s a family affair; one-third of Vietnam’s then-82 million live along the coastline of the narrow country so all ages are comfortable being on the water.

As I paddle the calm sea this early morning I ponder a question that’s been stuck in my head since landing in Hanoi: Why are we here? Good question, and not so dissimilar from the very query posed by quivers of young soldiers who arrived here against their better judgment 35 years before.

Then, Vietnam was off-limits to visitors other than those in uniform. Today it’s high on the list of tourists from around the globe, adventurous and otherwise. You see them — Europeans, North Americans, and plenty of middle-class Chinese — around-country: On day-trip boats touring HaLong Bay, climbing down from tour buses in Hanoi, visiting the sites of famous battles like Khe Sanh and Hamburger Hill. The Communist government in Hanoi accepts these strangers, if reluctantly, for the $2 billion they carry in-country with them each year.

What is it that attracts us to this place not-so-far-removed from war, a country where the lone main road is still pocked with bomb craters, and the victors suffering one of the world’s worst poverties, a place – especially the North – that was for so long regarded as enemy territory? Morbid curiosity? (At the sites of famous battles vendors peddle dog-tags, bullets and coins dug from the bloody soil.) What is it we are to make of these people along our sea-route who were not so long-ago regarded the enemy? And what must they make of us?? (The tourism boom here interest makes me wonder how long it will be before we are headed back to Afghanistan, not to fight but to snake in lines through Al Quaeda’s caves, visit the prisons in Kabul where John Lindh Walker was captured, maybe even – one day – to see Bin laden himself, whether in a mausoleum –cum Uncle Ho — or wax museum.)

L – These kids were paddling their way to school; home is a floating house rafted together with others and hidden from the sea’s wildest elements behind tall limestone rocks.

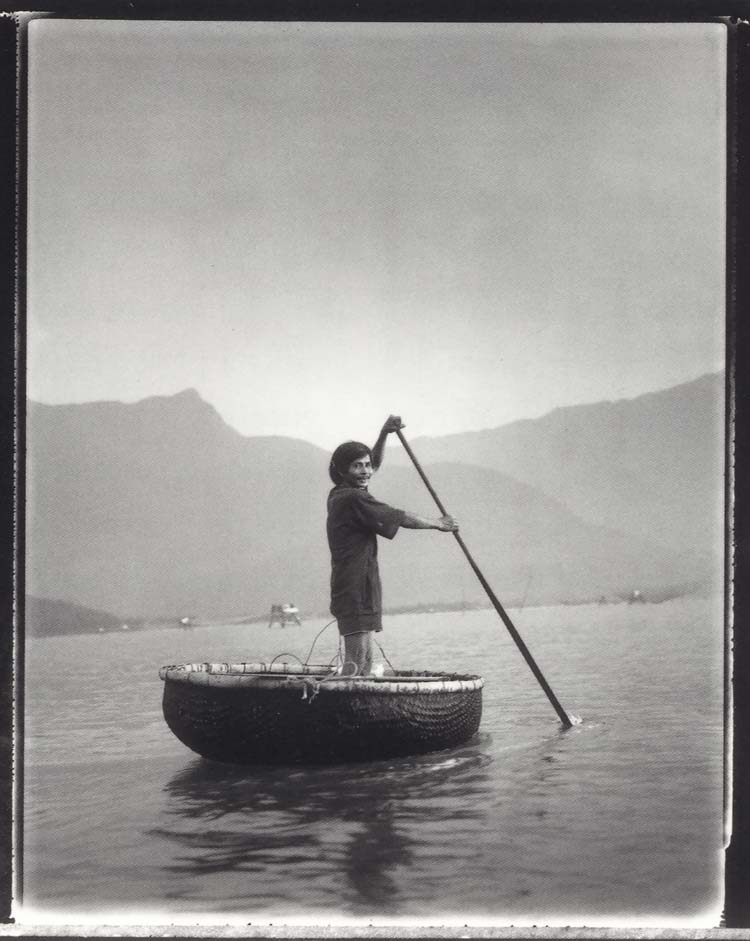

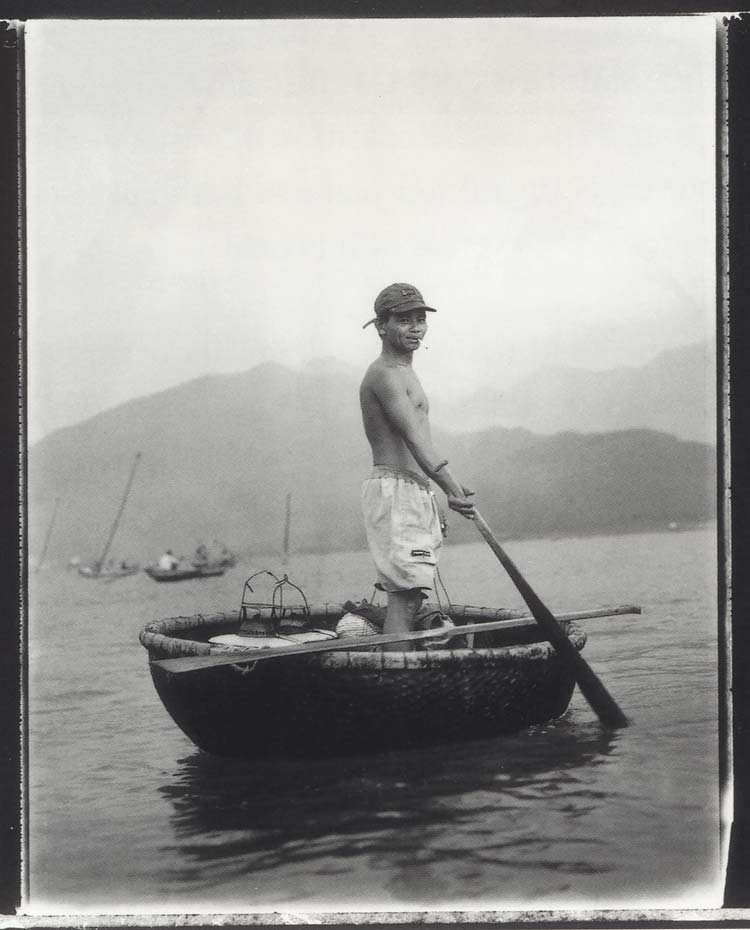

R – Life aboard a floating house has advantages (live fish for dinner are kept in cages just below the entry to the home) and disadvantages (tough place for a dog to take a run). This woman’s front porch boasts one of the classic round boats they use to get around calm waters. Sealed with tar it leaks just a little; we sometimes saw them far out to sea, many miles from home.

Make no mistake. Vietnam is no Thailand. Not a place for backpackers and ravers, sex tourists or wife-seekers. While beautiful and steeped in history, it is the poorest country in Southeast Asia (in part thanks to the U.S. embargo which lasted until 1996). While seemingly content, the people here are among the most impoverished and oppressed in the world. The government in Hanoi has little patience with the kinds of freedoms we take for granted, like speech, religion, press. E-mails are alleged to be monitored, outspoken Buddhist and Catholic leaders jailed without charge, anyone speaking or writing ill of the government – to jail. As a visitor you get a 30-day visa, that’s it, over and out, no lingering, no hanging-out, no moving in.

Travelers here have a tendency not to see the real country, despite their best intentions. Whether traveling individually or en masse, contact with the Vietnamese is usually from behind a bus window. What do we really know about Vietnam today, especially the North? That lacking is exactly what drew me, just how much we do not know about how these people live, post-war.

My own exploration came with certain handcuffs. Not just the 24-hour-a-day monitor who followed us every step, but dictates about where we could and could not go, who we could and could not speak with (“only truth-tellers,” our monitor advised). Despite these constraints, every stroke of the way I remained focused on this: What must these folks think of us?

One of my favorites scenes as we paddled along the coast were these elegant fishing nets strung from simple huts. The poles lower in from the corners and the nets sink below the surface; when it is pulled back up, out of the water, hopefully it is filled with fish. A rock weight at the center of the net forces the fish to roll into a narrow slit where the fishermen collects his catch. Often a husband and wife will spend more than 24 hours in the hut, raising and lowering the net through day and night.

uring a typical day, paddling 25 miles on a mostly-calm sea we passed children clamming in the shallows, a husband and wife net fishing in the middle of a wide bay, men in boats chipping mussels from the rocks. They use the sea like a piece of farmland, cultivating every corner. Signs of man float all around: plastic bags, playing cards, rubber thongs. During a typical day, paddling 25 miles on a mostly-calm sea we passed children clamming in the shallows, a husband and wife net fishing in the middle of a wide bay, men in boats chipping mussels from the rocks. They use the sea like a piece of farmland, cultivating every corner. Signs of man float all around: plastic bags, playing cards, rubber thongs.

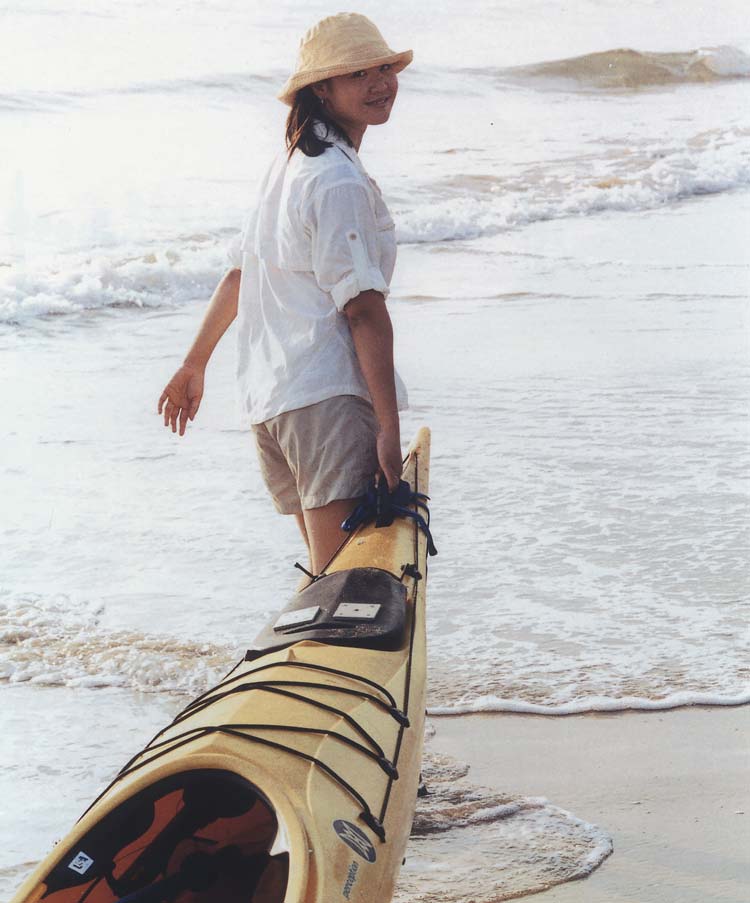

At midday I paddle alongside Ngan Nguyen, the most important of our five-person team. She had fled Saigon with her family on the last day of the war in 1975 (her father was a helicopter pilot with the South Vietnamese Army). That harrowing escape was followed by a month-long adventure at sea which eventually delivered them to New Orleans. Her most vivid memory of the fleeing is an elderly woman dying onboard on the way to the Philippines, her body dumped unceremoniously into the ocean. Sick with measles herself, Ngan feared if she got any more sick she too would be dropped overboard. Willing herself well marked a determination that has shaped her 29 years.

Including Ngan had been an imperative for me (I interviewed 60 candidates before choosing her . . .) for her knowledge of modern Vietnam, especially the issues of poverty and the environment, as well as her ability with the language. With her along we’d be able to truly talk to the people we met – dozens each day – without having to rely on government translators. Getting her into the country had not been easy.

Until just a few weeks before we arrived in Hanoi it was uncertain if the government would grant her a visa. It demanded she provide a list of names and addresses of all her family still living in Vietnam, an intimidation she’d never experienced during prior return trips working for UNICEF and Oxfam International. By allowing her to accompany us the government knew it was ceding a certain control.

A curious blend of self-described Vietnamese princess and all-American girl Ngan was educated at Tulane and the Fletcher School of International Policy in Cambridge. As comfortable at high tea at London’s Four Seasons as on a hard-packed earthen floor in Vietnam drinking from a soiled cup she self-mockingly describes herself as a “delicate flower.” Though reluctant to address the many personal dilemmas presented by returning to the homeland she’d fled as a child, on some days I would see her step back from her loud, brightly-clad American brethren, seeming to be ashamed to be affiliated with us. Other times I saw her repulsed by the insensitivities of Vietnamese her age we met along the route. Demanding, caring, charismatic, she was a perfect point-person as we prowled the coast in our plastic boats. Whenever I tried to pin her down – “Are you feeling more Vietnamese, or more American today?” – she demurred. “I’m a blend.”

“It was hard at first, of course, because we did not feel terribly welcome,” she says about her family’s first days in New Orleans. “Teachers couldn’t pronounce my name, so they never called on me. I was nicknamed ‘Happy,’ because they thought I was always smiling.

He looks away when talking about the racism that greeted them. “Initially we lived in a neighborhood where we were the only Vietnamese and whenever a dog in the neighborhood was missing the neighbors knocked on our door, assuming we must have eaten it.

“It wasn’t without some humorous moments. When I was a teenager I was teaching English to an older women just arrived from Saigon. We were at her house and she had made a dish for lunch and insisted I eat it. I didn’t like it, didn’t think it tasted good, but to be polite I ate it anyway.

“A week later I took her to the grocery store to do some shopping. When we walked up the aisle selling pet food – you know, canned dog food – she stopped and showed me the variety she’d put into the dish we’d had the week before.

“She thought dog food was . . . well . . . dog.”

A TOWN CALLED VICTORY

S

mall, silvery fish jump by the hundreds over my bow as we pull into a channel dividing the island village of Cong Dau Ty. People have lived on these distant islands, far to the east in Halong Bay, for centuries. This one was most recently repopulated in 1960 when the government resettled it to get people off an-already crowding mainland. The town’s name – which translates as “Victory” – came from residents having successfully participated in the wars that beat back the Japanese, the French, the Americans and, finally, the Chinese. (Reminds me of a line in Apocalypse Now, when Captain Willard remarks there are only two ways for North Vietnamese to go home: “With death . . . or victory.”)

Pulling my boat onto the muddy tidal flats I am greeted by a man in a blue zip-up pullover, green pants cuffed high to avoid the muck and blue plastic sandals. Thin, with a thick shock of black hair and prominent, tanned cheekbones, he introduces himself as Toan, 30 years old, from Hanja, a small village on the mainland.

Turns out he’s a kind of traveling alternative-medicine man he owns no boat and no home, drifts from town to town, Johnny Appleseed-like, carrying only a big burlap bag packed with various woods, roots, leaves and seeds he uses to cure everything from kidney stones to malaria, strokes to ailing livers, skills taught him by his grandfather. In Victory he is living in a borrowed stucco house on the opposite side of the strait; he invites us to paddle him across to see his herb garden and watch him prepare some medicines.

His borrowed house is surrounded by neat gardens, fertilized by ash. Palm trees rise on the hill behind. A smoky fire helps keep the bugs away. On the porch hang a worn hammock and his clothes – three pairs of pants and three shirts. A pair of doorways enter the white stucco building, though there are no doors. Inside is just a bed, draped by mosquito netting.

His medicines are neatly stored around the room. On a rack above his bed small plastic shopping bags are filled with various herbs and wood shavings. On the floor a newspaper is covered by a neat pile of what looks like finely cut tea. In the open rafters are stuck big, gnarled tree roots and limbs.

He has a mission, to ready nine daily portions of a concoction for a client suffering from bad kidneys.

He lays out nine perfectly square pieces of newsprint on the cement floor and begins. From one plastic bag, then another, he scoops a seemingly random pinch of crushed leaves, ground roots and herbs into neat piles on each paper. Reaching deftly beneath his straw mattress he pulls out a straight-bladed machete, then wrestles a twisted tree root down from the rafters. Resting one end of the root on the floor he methodically whittles it down to nothing, talking all the while, barely watching what he’s doing, expertly avoiding shaving flesh off his leg while he hacks.

He’d been in the Army until he was 23, fighting against the Chinese near the border at Mong Cai, a conflict that lasted into the 1990s. Like so many people we had already met in the north he had tried to escape the poverty and desperate times that still wrack post-war Vietnam. He tried several times, by boat, but was caught and returned each time. In retrospect he is glad he wasn’t successful. “There are so many poor people here who can’t afford the help of a traditional doctor, it is good that I am here. I am better and more affordable.”

One slightly odd thing is that he chain-smokes menthol cigarettes, lighting one from the other, even as he chops his herbs and roots and trunks and talks about the efficiency of such medicines and how they can cure everything.

I wonder about lung cancer? What does he recommend? I ask him if he’s ever tried to stop smoking. He says it is the kindness of his patients that keeps him smoking, since many of them pay him in cigarettes.

“The only thing to make you stop smoking,” he admits, “is willpower.”

Curatives prepared we paddle back across and follow him up a crushed-dirt path past neat cement, nearly square houses and curious stares. These villagers have never talked with, nor touched the hand of an American. During the war Halong Bay was heavily bombed, in part because it was home to the Ho Chi Minh Sea Trail, over which weapons, ammunition and food were passed by boat to overland fighting units.

We are welcomed into the home of Cua, 63, and his wife, Loi, 62. He is dark and wiry and full of spunk (or is it the morning’s rice wine?). She is striking, wearing a black velvet scarf, a yellow sweater pulled over a pink t-shirt and brown flowered pants. Both are barefoot, sitting cross-legged on the cement floor. Her teeth are stained deep maroon thanks to a life’s addiction to chewing betel nut. He pulls off his hat to show us his shiny black hair. “See I am young,” he shouts, “and plus, I still have all my teeth!” — a stretch in any language. The bottom row is a picket fence of five long, widely separated teeth, the top row just a trio, each sticking out nearly perpendicular to his face.

L – Since my goal on all of these expeditions is to share the stories of the lives of people met along the way we politely invited ourselves into as many homes as possible. This woman’s wall is covered with Catholic icons; C – her daughter and son say admit they put less faith in religion and more in freedom.

R – This man braising burrs off rebar to be used in the manufacture of cement boats used to move rice up and down rivers and canals would later show us severe burns on his back, which he said came from the use of Agent Orange during the years of fighting. His smile was still genuine, despite that we were from the country that had decimated his country and injured his body.

Above the family altar (requisite in every Vietnamese home, used for daily prayers and celebrations of annual death anniversaries) delicate red-and-yellow paper mobiles blow in the sea breeze. A black-and-white photo of the couple on their marriage day hangs next to certificates from the government thanking each of them for their efforts during the war. In the next room, above a child’s bed, posters of European soccer stars (Baggio, Zidane, Ronaldo) are pinned to the wall.

He offers us small teacups filled to the brim with rice wine. Sweet, like vermouth, he throws back cup after cup and talks more and more excitedly. He confirms the history of the town’s name. “Because we kicked the French, then the Americans!” He is smiling, nearly shouting. As his voice grows louder his elegant, smallish wife whacks him on the arm, saying, “Tone it down, these are our guests.” She’s afraid he’ll insult us with his talk of “kicking the Americans.” We assure them we are not offended.

“I don’t get a chance to express myself very often,” he argues. “I want them to hear.”

“We were bombed here during the war and hid in caves. It made it very difficult to fish!” He remembers the first bombing – April 1967 – and the fact that two American planes were shot down “five miles from where we sit.” He says the only Americans he’s ever seen before us were those two pilots. One was captured, the other shot when a gesture of “putting his hands up” was misunderstood as reaching for a weapon.

Like all of the people we’ve met in the north, they bear no animosity towards Ngan who they quickly suss out as a southerner.

“We are all one people today,” the old man says, pouring more drinks.

The doctor sits on the floor next to me, pouring tea, alternating cigarettes with long drags off a bong-like tobacco water pipe. Paid for his services with cigarettes and wine he doesn’t stint on either. The old man unwraps the bundle handed him by the doctor and his wife dumps one of the packages into boiling water. Once cooled he slurps it down from a big bowl in one big gulp. Rubbing his kidneys he pronounces himself “improved.”

With that, he stands to retire, exuberantly kissing me twice on each cheek as we back out the door. Outside the noon sunlight is dimmed by clouds and midday wine.

ESCAPE INTO CAT BA

T

wo days south of Victory we paddle into the fishing port of Cat Ba – the largest island in Halong Bay – accompanying a widening stream of fishing boats. It is dusk on a Saturday night, quitting time, but I am surprised by the crowd hustling to port. As we close in on the fringe of the harbor where 5,000 live aboard boats Ngan’s face takes on a look of horror, as she mouths, “Oh . . . .my . . . God!”

It’s like a scene out of Waterworld crossed with Escape from New York. Scratchy rock music blares, fireworks explode, smoke mixes with mist. Fast-moving speedboats zoom in and out nearly splitting us in two. We are cruised by a couple punks in a stripped-down metal skiff circling round and round, seeing just how close they can come, a wild look in their eyes. Flames of cook stoves flare from the on-deck kitchens of 3,000 boats. A Navy patrol pulls up alongside us, siren bleating, machine guns unsheathed, spotlights rotating. As the darkness extends, boats continue to arrive from the sea, all headed into the maelstrom of noise, diesel exhaust, garbage and fish sauce. As daylight’s last glimmer flickers the scene grows more ominous.

We have arrived in Cat Ba at a bizarre/fortuitous time. The next day the town will celebrate the 42nd anniversary of Ho Chi Minh’s visit. He had come – April 1, 1959 – to give his blessing to the fishing port, its industriousness and to encourage the people to protect Vietnam’s shores from the enemy, then the French. Each year it is the biggest fest of the year, outside of Tet, celebrated by speeches, traditional music and floats and costumes in the town’s main square.

The next morning as we paddle towards shore we hitch a ride aboard a rusty ice-maker cruising the port like some kind of floating Good Humor Man.

Nothing in this place – not fish, rice wine, politics, even Uncle Ho — is more important than ice. The boat’s owner, Hoai, offers more sweet rice wine as his iceboat cruises the alleyways looking for customers, ranging from small family fishing boats to big commercial squid boats that buy seven tons of crushed ice at a time.

A half-dozen workers hoist 70-pound blocks of ice from the hold and onto the deck where they are snagged with metal claw hooks by a pair of muscled strong boys – flat-nosed, giant-biceped 20-year-olds wearing matching yellow “PlayGuy” t-shirts and rip-off Nike thongs. They take turns lifting blocks over their heads and feeding them into an aluminum chute that directs the crudely crushed ice into proferrred wicker baskets or directly into the hold of the bigger boats. The grinder is run by an engine attached to the boat’s roof, jump-started by a hand crank and stoked with ice chips while running to keep from overheating. Its incredible shaking and racket make conversation difficult.

Hoai shouts his life story over the cacophony. It ends, after a fashion, with his graduation from Hanoi’s prestigious Ho Chi Minh College in 1991 with a much-desired economics degree. The very next year he made his first attempt to escape his homeland.

In the mid-Eighties, thanks to a combination of the high cost of war and corruption, failed cooperatives, embargoes, drought and the end of the Cold War the country plunged into abject, abject poverty, which continues today. Into the early Nineties anyone with access to a boat – or money to afford a place on one – tried to flee Vietnam.

Many were caught by the Vietnamese Navy (motivated by a cut of any fine levied). Some got away. The rest – like Hoai — ended up in giant refugee camps on the outskirts of Hong Kong, where they lingered for a year, two, three or four. After two years behind barbed wire Hoai applied to return to Vietnam. He paid a fine, and now owns his own business, which earns him $2 a day, on a good day.

He is 40 years old, but feels it’s too late to change his life. His hope is for his family. He admires Americans, he says, for their kindness and intelligence. We ask if he doesn’t see any irony in being so complimentary and respectful about a nation that not so long ago attempted to bomb his homeland to kingdom come, killing 1 million of his brethren along the way.

“That was not about the people,” he explains. “That was about governments. I know the people of America are very good. They love their families just like the Vietnamese families do. I cannot hold you responsible for what your government did.” He refuses to talk about his own government and doesn’t want us to photograph him, or video his college identification card, for fear of retribution if his image – or words – are reported.

It’s not the first time we’ve run into a reluctance to be quoted, or filmed. Along with Escape, the two most repetitive themes we’re picking up on are Oppression and Forgiveness. Yet despite their dire straits, we hear not one word of animosity, towards us as Americans. It would be easy for them to be bitter, understandable, actually, even expected.

Paddling away from Hoai, the raucous festival celebrating Ho’s visit is heating up onshore. I’m curious about Ngan’s take on the leader still revered here in the north. Given that members of her family had been killed, jailed and “reeducated” during and after the war he fomented she is not a big fan of the man, or in agreement with his followers.

“After 1975 everyone in the country was demanded to hang a picture of Uncle Ho in his or her house,” she remembers.

“When I came to visit my grandparents in 1991, in their small village an hour-and-a-half outside of Saigon, we went to a café where the owner was a friend. He had replaced the required photo of Uncle Ho with a poster of Bon Jovi. Apparently it was quite popular to do in their neighborhood. It was quite a shock when I looked up, expecting to see Ho Chi Minh, and instead there was Jon Bon Jovi.”

INSIDE THE VINH MOC TUNNELS

I

took a half-dozen steps down into the pitch-black tunnel and nearly turned and ran back. The cheap aluminum flashlight I’d been handed before entering was barely sufficient to light up the musky cavity that dropped as deep as 60 feet below the red clay surface. Though I could still make out the pounding surf of the South China Sea it was no great comfort. As the height of the ceiling dropped to five feet and the tunnel narrowed, I kept walking.

Though we’ve been attempting to veer our days and our experience away from war, it is difficult to avoid here in the DMZ, the demilitarized zone that literally split the country in two thanks to the Geneva Accord of 1954. We are just a few kilometers north of the dividing line, the 17th Parallel, and reminders of war are everywhere: The simple fishing village we kayaked into today – Vinh Quang – was the site of one of the worst days of the war, with 345 locals killed by bombs and napalm on a single day in June 1967.

Around that time 250 of the nearby villagers of Vinh Moc put their heads and hands together to dig this, the most elaborate series of tunnels in all of Vietnam, by hand. Offered the option of fleeing further to the north, they had refused, preferring to stay close to home and lived mostly underground from 1967 to 1972.

The digging took 18 months. There was no grand architect; a half-dozen families started digging from different directions through the sticky, red laetrite. In the end, there were 13 exits, including a half-dozen that emptied through heavy jungle foliage onto the sea. Each family – at its most-populous, 380 men, women and children lived simultaneously below the ground here – was given a living space as big as a single mattress. Many died from disease due to the humid, dank conditions, especially children who feared leaving the safety of the tunnels for even an afternoon. A maternity room where 17 children were born during the two years when the town was bombed nearly daily by American B-52s. A school occupied one thin sliver dug into the wall, as did a half-dozen freshwater wells. Cooking vents were dug deep into the soil to avoid tell-tale smoke from escaping and alerting overhead planes. A meeting hall where they performed song, dance and theater to keep themselves from going completely nuts while living underground for weeks on end. An emergency ward, long and dank, where they patched-up Vietcong soldiers.

The most harrowing sight I saw, once my eyes adjusted to the dark, was the first room we passed: A narrow slot dug into he mud called the Guard’s Room. An armed solider had sat there 24 hours a day, on lookout for the enemy sneaking down inside. What made it so spooky was that I knew that American and South Vietnamese soldiers had tried to sneak into this most intimate of hideouts – I couldn’t imagine a more heart-stopping assignment.

Emerging onto the sea through a narrow slit in the overgrowth was a relief, physically and emotionally. Walking over the top of the tunnel system it was hard to imagine the sophistication that lay below; similarly, it was hard to imagine that the bomb craters dotting the ground’s surface didn’t succeed in collapsing the whole thing into itself.

Just beyond where we had entered the tunnel we fall into conversation with a couple in their 70s who helped dig the tunnel and lived in it for most of six years. Their 33-year-old son – handsome, wearing a flowered shirt – was born in its maternity ward.

They’ve just walked into the yard of their simple, wooden, and neatly-hedged home. He carries a small basket of fish, she a rusted metal scale. Today their life has a simple rhythm, fishing and selling their modest catch in the local market. After an hour’s conversation – during which he does most of the talking, animatedly, using sea-roughened hands to highlight his descriptions – I ask if they hold any animosity against the enemy that forced them to live below ground for most of six years.

“I only remember the days of peace that came after,” he says. Even in the places hardest hit by the war the Vietnamese – unlike many Americans – have long ago moved past the war and onto the future, whatever it holds. Perhaps because they won, more likely because their continued poverty does not allow much time for debate or reflection.

I have one very base question for them: How did they eat during those long days in the dark. Obviously they couldn’t grow rice given the almost daily bombings; I wonder if he was somehow able to get out and fish between bomb-droppings. “We didn’t have to,” he admits, “Every day they would drop a bomb in the sea and the shore would fill with freshly-killed fish.” He and his friends would slip out at night and collect baskets-full, enough to feed all the tunnel dwellers.

Polly Green, me and Ngan Nguyen make a historic paddle on the Ben Hai River which for 21 years split Vietnam into South and North.

PADDLING THE 17TH PARALLEL

A

blur of sea, highway, beaches, government hotels, impossibly narrow houses and fish markets are strung along Highway 1, the lone road connecting north to south. Halfway down the narrow country we put our kayaks onto the Ben Hai River for a symbolic paddle along the 17th parallel, the man-drawn border that for 21 years split Vietnam in two.

A small boy and girl walk hand-in-hand on the rusting metal bridge crossing the river. Beneath it, a fishing man in an army-green shirt and pith helmet trolls from a tiny wooden boat. Fields of rice spread on either side of the river, an extremely idyllic picture of what was one of the most contested sites of the war, denuded by napalm and herbicides, littered with the graves of thousands of soldiers.

When we arrive at the river’s banks Ngan is quite moved, covering her tear-filled eyes and walking alone along the river. I catch up and ask why she is so moved. Had she not expected this place to feel so powerful? “I think I’m overwhelmed because I always imagined arriving here from the other direction. Arriving from the south, from my home, into the north. This feels very, very foreign to me. And the fact that three million people are dead because of this imaginary line . . . . when you stand here you can’t help but find pity for everyone involved.”

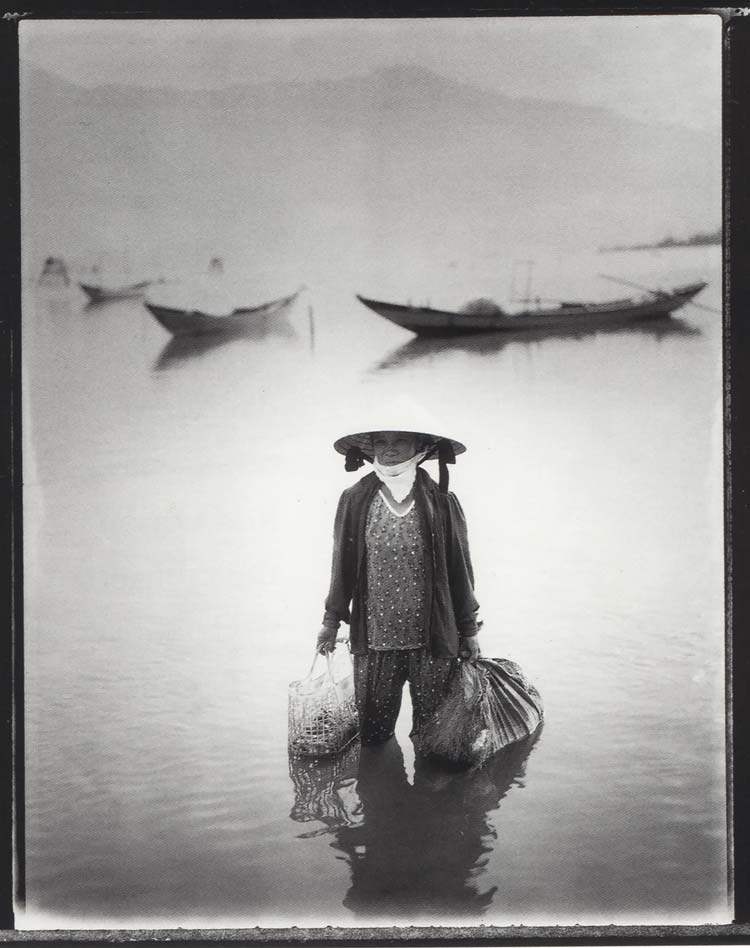

Fishing boats leave the beach early in the morning and return before noon; this woman has the unfortunate job of having to untangle all of the fine line used that morning.

We are greeted at the bridge by another in a string of Communist Party officials who have welcomed us each time we cross into a new province. This is our eighth (ninth?) province and the reps have ranged in age, gender and verbalness. Some shake our hands and move on, others have joined along with our monitor Linh and followed us for a day or two. This morning we are pleasantly surprised to be introduced to a sweet young man from Quang Tri named Luan.

It turns out he studied at the same school in Hanoi as Linh (English and International Studies), but he is instantly different from the other party officials we’ve met, for a simple reason: He was born in the South. “My father was a teacher,” he explains, “and during the war, despite that our family house was destroyed by bombs – twice — and we were forced to flee to Danang, we were officially neutral.” He joined the party as a teen he says, without pressure.

I am struck, standing along this historical border, by the fact that the three Vietnamese standing beside me – Linh, Ngan and Luan – grew up at the same time in Vietnam, under very different circumstance. Linh’s family retreated from Hanoi to an uncle’s country house 60 miles outside the city; Luan’s family home was bombed, forcing them to move to Danang; Ngan’s family fled all the way to America. The war wreaked dissimilar forms of havoc on each yet united them in one way: Unlike their forefathers – who have been at war on these lands for literally the past 1,000 years — none wants anything to do with war no more.

DRINKING WITH THE ENEMY

T

It’s a Wednesday night and we’re sitting with Linh, in chairs near the beach in Sam Son slowly getting trashed on Tiger beer.

Even at dusk Linh wears his blue-mirrored sunglasses. A pair of cell phones anchor his belt. I’ve jokingly taken to calling him Elvis, for his slim resemblance and that his favorite karaoke song is “Love Me Tender.” Thick black hair tops his handsome if pudgy face; his thumb nails are more than an inch long, a sign to anyone who’s interested that he’s a member of the leisure class. When I first met him he told me his priority was to make sure we met only Vietnamese who “told the truth.” A savvy government-lifer, he was three years old when the war ended. He admits he is as close to a real Communist as we will meet. I tell him I’m not convinced there are many true believers left, that like much of the rest of the world Vietnamese are motivated by the same dream — the American Dream, for lack of a better metaphor — of better pay, bigger house, brighter future.

Cracking open his fourth beer he says, out of the blue, “The goal of the Communist party now is to make people love communism. I love Communism!”

I ask him if he’s drunk.

“Not yet. But I hope to be soon.”

I ask if his father – now 66 – had been in the military or government. “He was one of nine children and had three brothers in the army, so he didn’t have to go. Plus, they were a rich family.” Turns out his parents were teachers; his father, geometry, his mother literature.

“My father’s parents were very rich but not my father. He was very carefree and bad-tempered, which was why he never made – or got – any money.” Linh has already told us one of his goals is to be rich.

“So you’re not following in your father’s footsteps exactly?”

“No, I am a smarter man than my father.”

Peter Getzels, the National Geographic filmmaker accompanying us, starts prodding, asking Linh about politics. Vietnam’s 9th Party Congress has just convened in Hanoi, where a new prime minister will be chosen. Apart from China, only Vietnam is attempting the acrobatic feat of creating a capitalist economy under the control of a Communist government. Clearly, it is suffering from a fear of great heights. Given a choice, wouldn’t Linh prefer a reformist candidate, someone promising change, to another tired old-line party hack?

His response is a classic deflect.

“I would just vote for a good leader.”

“C’mon Linh, that’s an escape,” pushes Peter. “Wouldn’t you be for someone who proposed change. Look around you, man, things here are not all that great.”

“Change is good,” admits Linh. “But only in the hands of a good leader.”

Another round is ordered. I ask Linh if he stays in government what job he aspires to. “Friendship Ambassador to the World!”

PERFUME RIVER

O

n an overcast day in April I slide my kayak into the wide, gray Perfume River and paddle west out of Hue, towards the green jungle hills of central Vietnam. As the brightly colored plastic boat slips beneath the city bridges heavy with early-morning bicyclists a few of the overhead passersby notice, stare and offer tentative, smiling waves of hello.

Paddling up this river was one of my most anticipated moments. From the romance of its name to the history of the imperial city it divides, the Perfume sparked a thousand images in my head, summing up the whole of Vietnam – love, hate, religion, civility, criminality, learning, censorship, escape, romance, beauty, peace and war. Especially war. The last fought in this elegant city in the 1960s – hand-to-hand — rubbled 1,000-year-old pagodas and turned the river into a morgue.

The big cities we had already passed through along our north-to-south route had been mostly sprawling, industrial, crowded, dusty. By comparison, Hue is lush, serene, especially when seen from the river. Flowering magnolias line the banks, fronting fields of coffee, beans and rice running straight down to the river. Women wash children on the cement steps of small, well-preserved pagodas. Old men walk a paralleling dirt path, hands clasped behind their backs. I paddle up to a trio of fishermen hand-paddling tiny wooden boats; one slides back a floorboard to reveal a couple dozen green-and-black striped fish he’d caught on his bamboo pole.

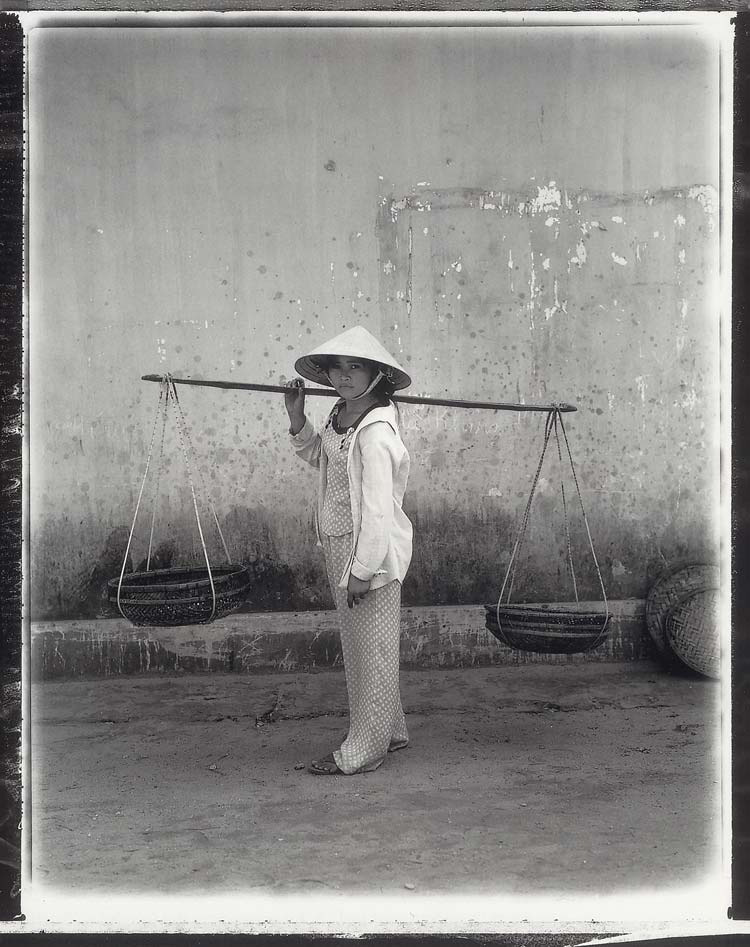

Mid-river is clogged with anchored barges. Families, dredging sand for cement. Mom and dad, a grandparent or two, use feet to turn wooden wheels, which crane heavily loaded buckets of sand up from the bottom. Son shovels the load into the floor of the low-riding barge, while his younger brothers and sisters’ play beneath the protection of a faded tarpaulin. When the boat is full it is motored to one of several drop-points along the shoreline where the sand is off-shoveled and carried uphill by women using poles and shoulder baskets. It is dumped into tall piles where it is once-again shoveled into waiting trucks. Like everything in Vietnam the work is simple, direct, backbreaking, never-ending.

The Vietnamese come off as resourceful, hard working, determined. Certainly an unrelenting opponent in any fight, especially one in their own backyard. They are also impoverished, frustrated, desirous of a better life, disappointed that a 26-year-old peace has not yet delivered prosperity. The country today is like a nation of bees buzzing inside a bottle, thrumming with repressed energy, ready to burst.

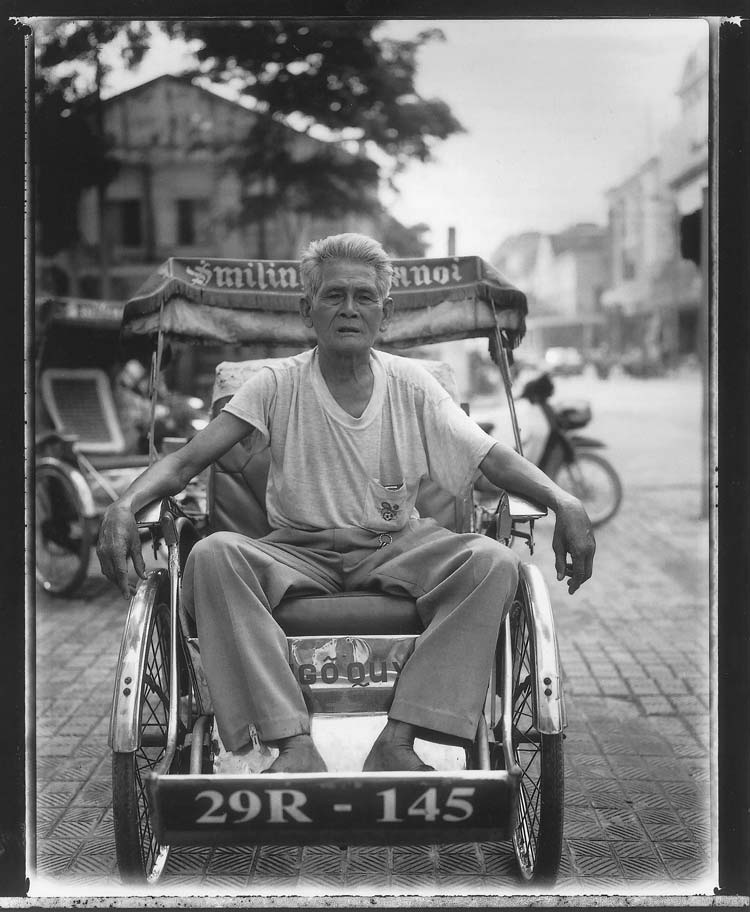

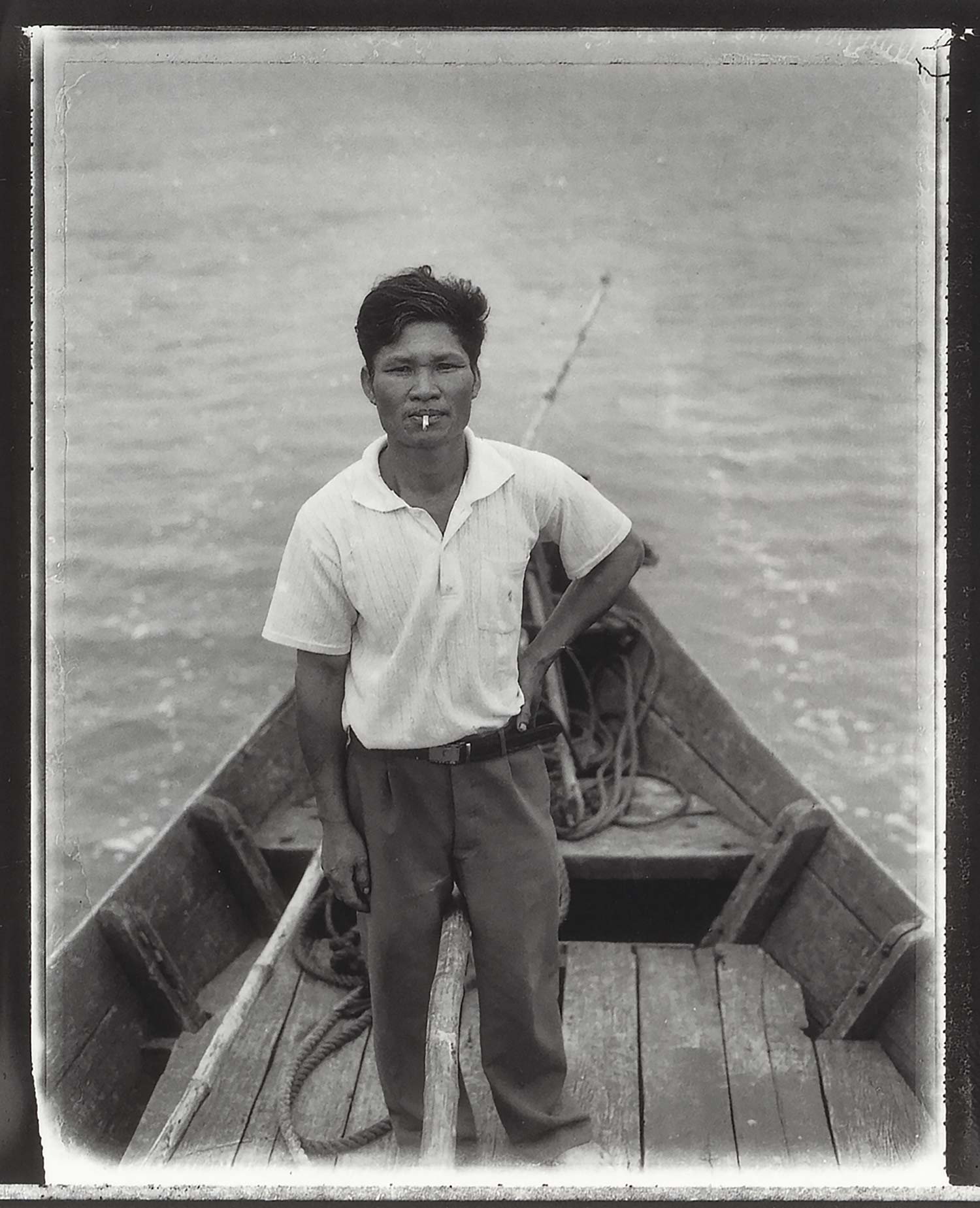

Photographer Rob Howard carried an oversized Polaroid camera with him on this trip and spent many hours with his subjects as we moved down the coast. The result were beautiful portraits of people at work, here a pedi-cab operator and a woman carrying fish to market in her twin baskets.

We stop along the river to visit the seven-story pagoda. Renowned for training outspoken Buddhist monks we’ve been told we may not interview the monks. Linh, backed by a local party official, follow along to make sure we abide.

Later I sit above the river with Linh and his colleague Lap, who has been helping us with ground logistics. Catching them in relaxed mode. I ask about their understanding of America and what it represents to them.

“You guys don’t like the idea of America – or what America stands for – coming to Vietnam, do you?” I begin. For the moment, other than growing numbers of tourists, there are less hard examples of Cultural Americana here than other parts of the world. No Hollywood movies, no McDonald’s. But, as everywhere in the world, we’re coming. Linh’s cigarette of choice? Marlboro Lights.

“No, I like everything American,” says Lap, without hesitation. “I like everything about America.” His parents are entrepreneurs in Hanoi, owning a leather-making shop.

“I disagree,” Linh says.

“Of course you do, you’re with the government,” Lap shoots back. Though the same age they are definitely not cut from the same ideological cloth.

Redressing his countryman with a dirty look, Linh continues, “I am happy to have Americans – and America – coming to Vietnam. But not the bad things.”

“Like what?” I ask.

“Like gangsters and killers and crime, things like that.”

“But don’t you have gangsters here?”

He changes the subject, but I push, trying to provoke some talk about freedoms, especially since we are here on the edge of a monastery where we’ve been told we cannot talk with the people we meet. I try to explain why democracy in the U.S. – despite its obvious flaws, like the death penalty, wasteful consumerism, environmental blindness and too much crime and prisons, etc. — is still a good system. That freedom – of choice, press, religion – is ultimately a better system than this one.

They both nod, seemingly in agreement, but I’m not convinced they truly understand the difference between the two systems.

Linh exposes a new piece of himself later in the day, after the woman sent out by the local party committee left to spend the rest of Sunday with her family. She would have been disappointed, if not outright pissed, to have seen his somewhat lax monitoring of us at the pagoda as we eventually did talk with a few monks, even filmed them, though not about anything remotely controversial. Linh realized the risk he was taking.

“I may need your help with a job in America if they find out,” he half-jokes.

DETERMINATION IN THE WEIRS

T

he central coast is hot – 105 degrees by 10 – so our paddling days have been starting at 5:30 a.m. A crowd of kids – up early, kicking a soccer ball up and down the beach long before school starts — helps us push off into the lagoon at Thuan An, east of Hue.

Weirs made of tall bamboo stakes stuck in the shallow mud stretch for miles, fences built to keep seeded crabs and shrimps inside the fenced-in areas. The scene is beautiful in its sparseness. Men and women in small boats pull in the nets every couple hours, all day long. From my boat I watch a guy constructing a dam from sticks and mud, pushing an empty metal can into the muck and pulling it up with his feet.

Access is through narrow breaks in the stakes; once inside it is nearly impossible to find our way back out of the maze. Red banners top tall poles marking the center of many of the farms, altars laden with incense sticks, candles, flowers, small plates of food, offerings of small wads of dong. A fisherman standing waist-deep in the shallows waves for us when he sees us struggling to find an exit and motions towards his home, a stilted shack with a rattan roof. Four small wooden fishing boats are tied at its base; they are home to 20 members of his extended family. When we paddle up they emerge from boats and all corners of the weir.

My main interest during all of our Oceans 8 expeditions, which took us around the world one continent at a time looking at the relationship between man and the sea, was to stop and meet the people we were passing. I was desperate to try to paddle one of their round boats and managed to one day; unfortunately all I could do was go around in circles, never quite figured out how to make a round craft go in a straight line!

The patriarch is a blind veteran of the war. His wife, their four sons, various spouses and a dozen small children all live on this little plot of saltwater. His sight lost just three years ago, what he remembers about American soldiers is that they ate their food from cans and “had very bad teeth.” The rest of his family have never met an American. All but two of the adults are illiterate, a rarity in this highly educated country. They can only afford for two of the dozen children to go to school at any one time. Bone thin, one son has what look to be severe burns on one shoulder – Agent Orange? A couple of the infants kids are covered with scabs and sores. They all wear the international uniform of the poor: Cheap t-shirts with familiar names, Adidas, Chicago Bulls, Coca Cola.

They are as curious about us as we are about them. These are boat people and they fully appreciate our means of travel. They touch our kayaks, crank the rudders up and down, are most impressed by the red-and-gray bilge pumps and sit on the bow and stern, rocking the boats up and down in the shallows.

They have worked this crab farm for 10 years; owned it the past three. It is seeded with baby crabs and they sell a single adult for 10,000 dong – 75 cents – in the market at Hue. They work it seven months of the year, on opposite sides of typhoon season. The other five months they live on their boats closer to land, protected from storms and winds. Though they own this plot of sea, they have no real collateral, making it impossible to get a loan of even $50 or $100 to buy a new boat, lease more sea-space.

The older boys take us out into the “fields.” From a narrow wooden boat a pair feed a fine net weighted at the edge by sinkers into the two-to-three foot deep water. One oars the boat in a rectangle around the 30 by 100 meter perimeter until all of the net has disappeared below the surface; the other feeds out the net while simultaneously bailing with a rusting army helmet. In an hour two more men have joined and they walk the perimeter through the muck picking up the net and plucking out crabs, some up to a foot-wide. They do this every couple hours, up to five times a day, in order to barely feed their extended family.

Ngan, Peter and I are invited into their stilted shack for lunch. Crabs, of course. While we eat they stare, laughing behind their hands at our awkwardness with the shelled critters. The elder brother takes my crab from me, skillfully picks out the tender white meat from the tips of the claws and hands it to me.

Sated, we paddle just a mile to reach the long barrier islands that border the eastern edge of the lagoon. A narrow sand isthmus that suffers annually from typhoons, rains and floods these islands are also home to the highest standard of living we’ve seen yet. “Fancy” (their word) homes are piled next to each other atop the sand dunes, two and three-story masonry constructions painted in pastels, with smooth tile floors, balconies, electricity, televisions, vcrs, cooling fans.

The reason for the riches is simple: Boats. Actually, it’s slightly more complicated. Everyone here has a boat. These big houses are here thanks to boats and good luck.

These islands are the closest spot along Vietnam’s coast to China’s Hainan Island. With favorable seas and wind, push off from here and 24 hours later you’re free. During the last days of the war – and into the 80s and early 90s – thousands of escapes were launched from these beaches.

One out of two families here has at least one relative who “made” it to the U.S., Canada, Australia. The money these relatives, known as Viet Kieu (outside Vietnamese), have sent back, from jobs as simple as landscaping or printers, have paid for these elaborate houses. (Two billion dollars a year comes into Vietnam from the U.S. alone, creating one of the country’s great post-war ironies: The very people chased out have now become a potent and valued economic resource.)

All this luxury did not come without risk. Those caught – and half were caught – were beaten, jailed or killed.

A grandfather in short pant pajamas invites us for tea inside his pink, two-story house with white-columned balustrade. His daughter fled to the U.S. 10 years before, and is married to an American man living in Florida. She sent back the $13,000 to build this house (an equivalent place in the States would probably run $250,000). While he is showing off his home, from the balcony I can see the stilted shack of the crab farmers we’d lunched with.

His only son, who tried to flee twice but was returned, explains that the money comes into the country as dollars and is turned into gold bars and saved until the amount needed to build a house is in hand. There’s no such thing as a mortgage here and few banks, one reason somebody is always at home in Vietnam.

I follow a sandy path climbing uphill towards the sea and stop at a blue cement house where a half dozen fishermen sit out the heat of the day. They range in age from 20 to 70.

The eldest has two kids living in the U.S.; his son in New Jersey works for a lawn care company. The old man is waiting for a visa to visit, which should come any day. His wife is in the side yard trying to wrestle a green glass bottle into the mouth of a reluctant water buffalo. I ask what she’s feeding the tied-up beast (used to cart sand from the beach). “ ‘La Vie,’ ” they laugh (the Evian of bottled Vietnamese water). The joke is, they are probably rich enough to feed their water buffalo bottled water. Truth is she’s trying to get the beast to swallow water laced with vitamins, “to keep him strong.”

One man on the porch, my age, tried to escape three times. He was caught and returned each time. It cost his family $3,000 each time to keep him out of jail. Was it worth the risk, the expense?

“Absolutely.”

PADDLING CHINA BEACH

I

t’s 90 degrees by eight, with no onshore breeze, a good day to spend offshore, paddling the 30 kilometers of sandy beach that runs from Danang to Hoi An, our last stop.

As we ready the kayaks, sweating in the hot sand, Linh sits in the shade with an ever-expanding table of uniformed military men. He’s buying them coffee, proffering cigarettes and showing them stacks of officially stamped faxes and letters and approvals. One of the officers, red epaulets and gold buttons glaring in the sunlight, gives me a surly look when I approach. Linh attempts to make an introduction, but they are definitely not interested.

The paper shuffle goes on for more than hour, as bad as we’ve experienced during the entirety of the trip. To get their final approval for something – kayaking the length of the beach – that was approved months ago.

When the confab finally breaks up I ask Linh, just under my breath but loud enough to be heard by anyone understanding English, “What are they so scared of? Do we really look like spies? Do they think are we going to share secrets with the world that it the doesn’t already possess?” I remind him that outgoing President Clinton arrived in Vietnam the previous November armed with U.S.-created satellite imagery as a means to help the country sort-out horrendous floods then wracking the Mekong Delta. What kind of vital information do these guys think we are going to gain from our kayaks that the world-at-large doesn’t already have in its hip pocket?

“I think what we’re wrestling with here is all about territorialism and protecting their own turf. What do you think Linh?”

Still within earshot of the cops, Linh goes pale, fearful they might overhear my audacities and rescind their approvals.

“We will talk about it later, okay?” he mutters.

“But don’t you think that’s it? That in this incredibly thick bureaucracy, nobody wants to take the responsibility for saying yes to something new, something that somebody else – some faceless superior – might question. I mean, where are the military sensitivities here, other than ego?”

“I think it might be something like that,” Linh admits, agreeing only to shut me up.

Finally we push the kayaks into the surf.

My teammate Polly Green, an international whitewater champion based in Durango, Colorado, and I keep pace ahead of the others and talk over the wind about her father, who’d been based in Danang during the war.

“For most of it he was in the Philippines,” she says. “But he wanted to come here. Requested to come, actually. The irony is that once he arrived it was as if he was in charge of a ‘gang that couldn’t shoot straight.’ Literally. Everyone on the base was required to carry a gun at all times; his guys were mostly geeks who’d never practiced. The whole time he was here he was most afraid he’d be accidentally shot by his own men.

“He has lots of photos from Danang, not just those pictures of battleships. My favorite is of he and a buddy in a bar posed with a couple Vietnamese women. He looks so young, so strong, so good. Despite that he hated the war, I think he really was empowered by being here.”

The coastal scene passes by without words. Past simple, dry fishing villages, fishermen in round boats seining offshore, small commercial boats coming and going. At midday we surf through six-foot waves onto a beach marked by palapas, and order plates of fried squid and Cokes, sitting in the shade on an idyllic beach for two hours watching the waves crash.

Back on the sea the sun grows more intense and a headwind picks up, making each stroke an effort. When we finally turn onto the Thu Bon River that leads into Hoi An it is with a deserved exhaustion.

At the mouth of the river I paddle alongside a small wooden boat and watch the incoming fisherman set a simple triangular sail. Set against a backdrop of perfect blue sky and a handful of small fishing boats motoring for home as the sun goes down it is a perfect way to pull into the 500-year-old port town of Hoi An, which translates as simply to meet the peace and quiet . . . .

Putting my hand on the side of his boat and hitching a ride into the wind I ask what it is he likes about his life here, in his boat, on the sea. His reply is simple.

“It’s the freedom,” he says, “the freedom.”

– EPILOGUE –

I have been to Vietnam several times, initially to scout the sea kayaking adventure and then six years later to get a glimpse of how things were changing. And changing they were, fast. More people, more commerce, more pollution, many more tourists. Whenever I asked locals though about what was Vietnam’s future, they all agreed: Watch China. As China goes, so goes Vietnam, whether it’s freedoms or economics, environmental regulation or military build-up. Vietnam is like China’s little brother, tucked geographically under big brother’s arm.

– CREDITS –

JON BOWERMASTER

Writer, filmmaker and adventurer, Jon is a six-time grantee of the National Geographic Expeditions Council. One of the Society’s ‘Ocean Heroes,’ his first assignment for National Geographic Magazine was documenting a 3,741 mile crossing of Antarctica by dogsled. Jon has written a dozen books and produced/directed more than fifteen documentary films.

NGAN NGUEYN

Ngan lives in New York City and is the mother of two. She shared a reflection of the adventure with us:

When Jon asked me to join the expedition, I came on board with much trepidation not only because I was a poor swimmer and had never before kayaked, but also because I wasn’t sure how people up North in remote regions would receive me, a Vietnamese American political refugee with a strong southern Vietnamese accent. But as I would soon learn, my fears were baseless. My team was made up of the coolest, most capable, group of adventurers who were at the top of their game. I knew I would be in good hands when I watched Jon fiercely negotiating our access to restricted coastal areas, Rob squatting in the middle of a busy street amidst the onslaught of motorcycles, cars, cyclos, and bicycles for that perfect angle, Peter hauling video equipment in a rickety boat that carried rare purple squid, and Polly battling one bad ass wave after the next.

Our A team was the first to bring kayaks into Vietnam. Kayaks were the most ideal vehicles to visit remote places and people that were beyond the reach of our government minders. We interviewed countless people in multi-generational floating communities, on rivers, and near caves and beaches strewn with Chinese artifacts from ship wrecks hundreds of years ago, and heard brutal tales of survival in pre- and post-war Vietnam. Every encounter was filled with warmth, curiosity, and enthusiasm. On numerous occasions, as our boat approached shore, women – some elderly, some maimed – rushed into the sea, pulled me off my kayak, and gave me tight embraces while they enquired about my life. Vietnamese hospitality never ceases to amaze me. We were offered tea and stories everywhere we went. Once, a malnourished family of five invited us into their makeshift home on stilts to share a meal of five small crabs.

There were too many riveting stories, but most memorable was meeting a couple in their 80s who started their married lives on a boat, raised their six children on the Perfume River, outlived most of their children, and opted to spend the rest of their days where they felt most at home: on water. From this boat, they witnessed the ebb and flow of the turbulent history of their country. They came from water, built their lives on it, and wanted to return to it.

Sixteen years after our journey, I still smile every time I see a kayak in Vietnam, knowing with great amusement how the first ones arrived and how much fun the party responsible for their debut had in such an incredible country.

ROB HOWARD

Rob continues to shoot still photos and video around the globe, based out of Margaretville, NY. He shares his memories with this video update:

POLLY GREEN

Polly lives life is as one big adventure, filmmaking, writing, and doing shamanic energy work in Bali, Indonesia. She recently reflected on the trip to Vietnam:

Barry Tessman was an adventure photographer, who I met on the Kern River in California. Barry and his wife Joy were my idols. Pictures of exotic remote locations adorned their cozy Kern River home, and I wanted to be them when I grew up.

Barry introduced me to writer, Jon Bowermaster, at a Salt Lake City Trade show. Jon was organizing a sea kayaking expedition sponsored by National Geographic, along the coast of Vietnam, and invited me along as part of the team. Barry was going to be the photographer on the trip, along with filmmaker Peter Getzels, interpreter Ngan Nguyen. Tragically we had to replace Barry as photogher just weeks before the trip began, after he mysteriously drowned kayaking on reservoir near his Kernville home. His death has never been explained, and will forever be a question mark. A great, NYC-based photographer, Rob Howard, joined the team.

We were not completely clear of tragedy. Hanoi was our rendezvous location and the team had assembled for our sea kayak expedition along the coast of Vietnam. On our first day in Vietnam, using the scissors from his first aid kit, team leader Jon Bowermaster, delicately removed the stitches from my shoulder one by one. Fresh from shoulder surgery, and my own brush with death(a diagnosis of stage 4 cancer), divine providence was on my side, or it just wasn’t my time to go.

An innocent looking blood blister the size of a quarter had popped up on my shoulder some months earlier. Successfully ignoring it, adopting my ignorance is bliss attitude, until a dermatologist friend strongly urged me to get it checked out. He wrote me an email saying, “this could be Class Six (certain death) Polly,” and he was right. Begrudgingly making a doctor’s appointment in between traveling, saved my life. The cancer was removed. Had it not been, the doctor said within the year I would have been dead.

But it was a fantastic trip and experience. Vietnam, all expenses paid! My job was to make sure the interpreter was safe, and paddle the filmmaker around so he could get his shots. Five weeks paddling behind National Geographic filmmaker Peter Getzels, was film school on the fast track. I intently watched his every move, my inner artist whispering, “hey Polly, we could do this.” Peter even let me take a few shots, and encouraged me to pursue a film idea that I had about women in whitewater kayaking.